One of my favourite crime history figures is Alphonse Bertillon, the French police officer and biometrics researcher who began work as a humble clerk and ended up developing a system for identifying criminals that was used all over the world.

A rather unpromising start

Alphonse Bertillon was born in Paris on 22 April 1853. His parents were Louis-Adolphe and Marie Zoë (née Guillard) Bertillon. His father was a medical doctor and an accomplished statistician. He co-founded the school of anthropology in the French capital, where he worked as a professor. Alphonse had an older brother, Jacques, who followed in their father’s footsteps and was also a doctor and became a renowned statistician. In contrast to his high-achieving family, Alphonse’s educational achievements were patchy and he failed to complete medical school. Keen to find a post for his 26-year-old son, Louis procured him a position in the Préfecture de Police in Paris (a unit of the French Ministry of the Interior), as a records clerk. His job was to copy the details of known criminals onto index cards. But Alphonse soon realised that he could do far better, and over the next two years, he developed his own recording system.

Using the knowledge that the structure of the adult body doesn’t change throughout its life span, and that no two individuals would measure exactly the same, Bertillon devised an anthropometric measuring system, later known as ‘Bertillonage’, which was based on the measurement of eleven separate body parts, including the width of the skull, arm span, and the length of the right ear and the left foot. In 1879, he presented his idea to the police department and it was formally adopted four years later. During the first year, Bertillon used his new system to identify some 300 habitual offenders. He published a complete guide to the system in a book, Identification Anthropométrique.

The ‘speaking portrait’

Once the suspect had been measured, the information was entered onto a card, along with additional information such as personal history, past convictions and other physical features. At a time when offenders were adept at changing their appearance through the use of disguise, facial hair and tattoos, Bertillon sought to overcome this by developing further innovations, such as a letter code for distinctive features, and classification charts of different eye colours, nose shapes and even facial wrinkles.

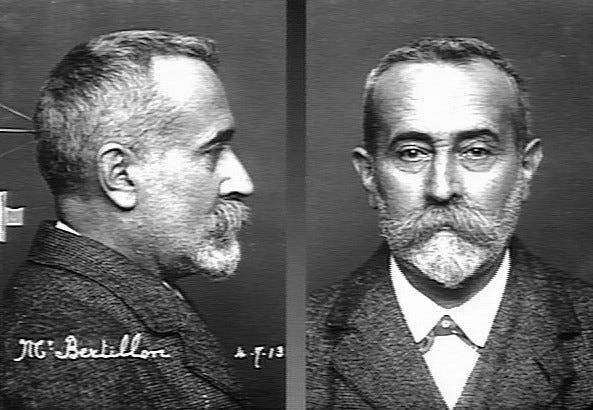

These details formed what Alphonse called the ‘portrait parlé’ (‘speaking portrait’). He later added photographs of the offenders, which became known as ‘mugshots’. He revolutionised previous attempts to photograph prisoners by developing a new method, which comprised taking an image of an individual’s profile as well as their face. The mug shot became the standard process for photographing suspects in 1888 and is still used today.

After officers visited the police headquarters in Paris and watched the process in action, Scotland Yard adopted Bertillon’s system in 1894. It was described in a government commission on the identification of habitual criminals as ‘perfect’, with the caveat that the measurements would have to be taken accurately. For my doctoral research, I investigated to what extent the system was adopted by regional detective departments. I found that, although Bertillonage was used in some borough forces, such as Manchester from 1895, it was not fully implemented, partly due to the lack of specialised equipment and the local expertise to use it. But also, the measuring system was soon superseded by fingerprinting, which was established formally with the creation of the Fingerprint Bureau at Scotland Yard in 1901. (Although fingerprints were added to his record cards, Bertillon never accepted that they were more effective than his measuring system).

Back at home in France however, Bertillon’s meticulous record keeping contributed to the arrest and conviction of serial killer Joseph Vacher, known as the French Ripper, in 1897. This confirmed the success of Bertillon’s portrait parlé and, by the end of the nineteenth century, his anthropometric system was used all over the world. Following the Vacher case, France’s national database was extended to several other countries, which is still in existence today and is now known as Interpol.

CSI pioneer

Alphonse Bertillon also developed new techniques in other areas of crime investigation, such as footprinting, ballistics and handwriting analysis, but his most enduring innovation was the introduction of crime scene photography. At crime scenes, he used a camera on a tripod which afforded him a ‘God’s eye view’ of the victim and their surroundings. He also created a grid to map the crime scene, on which he recorded the position of objects and furniture within the location.

Alphonse Bertillon’s achievements are not only remembered today by police historians and criminal investigators, but he has also been immmortalised in detective fiction. Such was his international fame that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle made references to his expertise in his stories. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, Dr James Mortimer states that Sherlock Holmes is ‘the second highest expert in Europe’. When the disgruntled private detective enquires as to whom is the first, Mortimer replies:

To the man of precisely scientific mind the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.

There are also references to Bertillon in Agatha Christie’s detective novels. In The Murder on the Links, Hercule Poirot laments that there are no fingerprints on the murder weapon ‘thanks to the publicity the Bertillon system has been given in the Press’. And, in The Secret of Chimneys, Superintendent Battle wires the police in Paris for the suspect’s fingerprints and Bertillon measurements.

Alphonse Bertillon died on 13 February 1914, aged 60. He pledged his brain to the Mutual Autopsy Society, which was dissected. His remains are buried in Père Lachaise cemetery, Paris. His legendary achievements are engraved on his headstone, on which he is described as the inventor of the anthropometric system. I visited his grave and it was quite emotional experience standing next to his final resting place.

There is an excellent exhibition dedicated to Bertillon’s pioneering work at the Préfecture de Police museum in Paris – you can read an account of my visit here.

Very interesting, and godo context. He is a very interesting character in the history of criminology. I wonder to what degree there were other parallel/similar efforts at criminal identification and also why was this becoming a pressing issue. Was there a rise in crime? Did ideas about the causes of crime change such that it was assumed that most crimes were committed by a small number of people? Did changes in infrastructure meant that criminals could have an easier time moving between places and committing crimes -- resulting in a need to identify if people had committed crimes elsewhere?

@crime&psychology recently wrote about Bertillon too. In case you are interested, https://open.substack.com/pub/jasonfrowley/p/the-incredible-and-sad-tale-of-grumpy?r=2bk4r1&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false