The beginnings of formalised and more methodical examination of crime scenes dates from the mid-1800s, with medical experts, police officers and early criminologists developing pioneering techniques such as trace analysis, fingerprinting and crime scene mapping.

The early days of CSI

As in many other countries, in Britain throughout the nineteenth century, crime scene investigation remained rather haphazard. When a suspicious death was discovered, the local police were usually called to the scene, followed by a doctor. The matter was then referred to the coroner, who organised a post-mortem. There was no preservation of the site, which would be trampled by the coming and going of many people, including ‘sightseers’ (the Victorians loved a good murder!). Potential evidence would be removed from the scene and kept at home, until the items were later produced in court, sometimes cleaned but, more often than not, still covered in blood.

The body of the unfortunate victim often remained at the scene until the coroner made arrangements for its removal to a nearby mortuary, or it was taken to a nearby building such as an outhouse, the workhouse infirmary, or even the local pub. It was common to wash the body prior to examination, presumably to make the experience more palatable for the coroner and jury members, who typically viewed the body in situ before the inquest proceedings began. The Bermondsey Murder in 1849, demonstrates the process.

After Patrick O’Connor’s body was discovered under the floor in the basement kitchen of 3 Minver Place on 17 August 1849, his body remained at the scene until the following day. The quick lime, which had been used in the mistaken belief that it would hasten the decomposition, was washed from the body before the post-mortem examination, which was performed on the kitchen table. The false teeth removed from the body were taken for safekeeping by the coroner’s clerk and later produced in court. The police searched the house, which belonged to married couple Frederick and Maria Manning, for clues and removed all incriminating items, such as the deceased’s clothing and his umbrella. None of these items were admitted in court as evidence. This was fairly typical of crime scene investigation at the time.

The first CSI handbooks

Four years earlier, in 1844, the first guidance for doctors when confronted by a possible murder victim had been published by William Augustus Guy, professor of forensic medicine at King’s College London. In the first edition of Principles of Forensic Science, Guy set out his advice for medical experts, rather than for the police. He instructed doctors to observe the location of the body, its position, the soil or surface on which it was lying, any nearby objects, and the victim’s physical appearance and clothing.

Almost half a century later, in 1881, Sir Howard Vincent, head of the CID at Scotland Yard, published specific instructions on ‘dead bodies’ in his Police Code and Manual of Criminal Law. Following a stint in Paris observing the more sophisticated techniques of French detectives, Vincent tried to reform investigative practice back home. Through his Police Code, which ran to sixteen editions until 1924, he sought to formalise the investigative practices and behaviours of the British police. Vincent emphasised that no one should touch the body before the police arrived, and that it should not be moved until a senior officer gave the instructions. In his advice on investigating a crime scene, Vincent included footprints and other clues which may be found on and around the victim’s person. He added that if a body was not identified, it should be dressed ‘as nearly as possible as it was in life’, and photographed prior to burial.

The art of tracing footprints

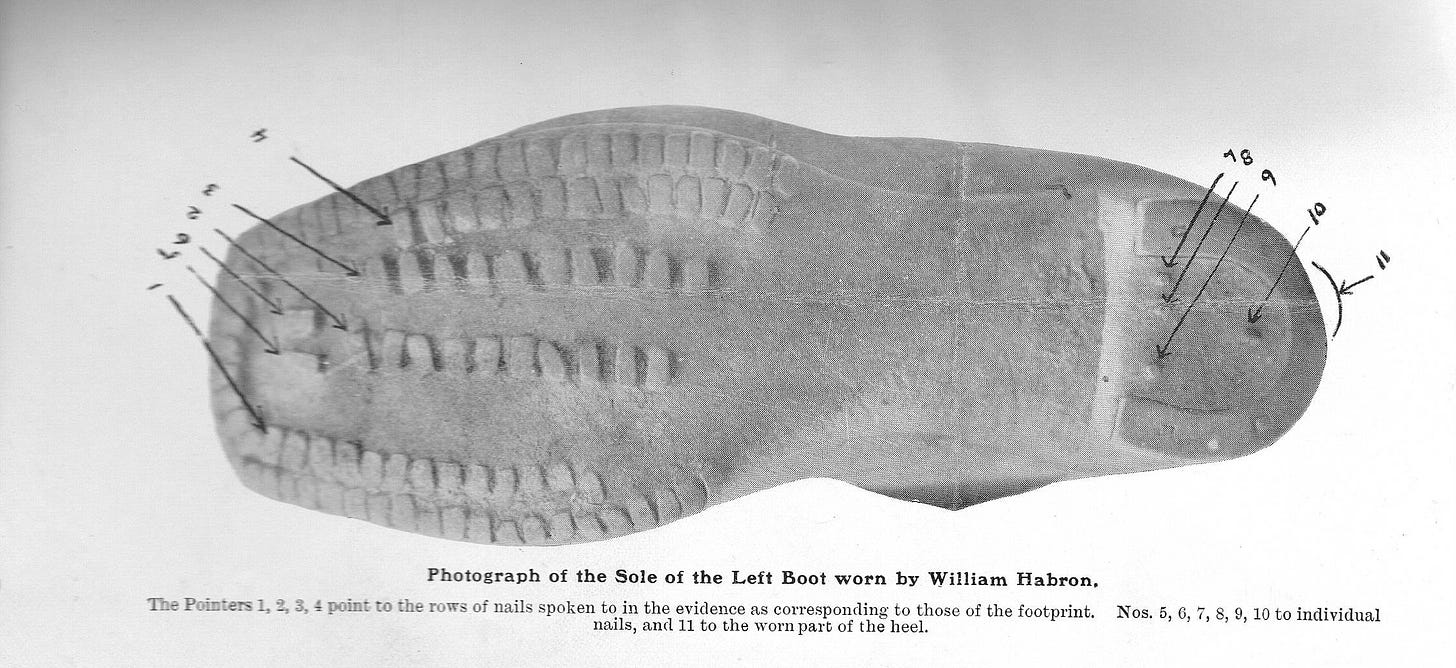

One CSI tool included in the Police Code is the examination of ‘footmarks’, in which it suggests making a model of the impression using plaster of Paris or Spence’s Patent Metal, and then comparing it with the suspect’s foot wear. The guidance warned of the potentially damaging effect of weather, such as rain, and advised covering footprints, in the event of an unexpected shower. This was exactly what Superintendent James Bent, of the Lancashire Constabulary, did in August 1876, whilst investigating the shooting of his colleague PC Nicholas Cock. When it began to rain, Bent covered the marks with a box. He later matched the footprints with the prime suspect William Habron’s left boot.

Later that same year, Superintendent Bennett of Berkshire Constabulary took casts of footprints found near the spot where Inspector Joseph Drewett and PC Thomas Shorter were shot, and these were used in evidence against the perpetrators Henry and Francis Tidbury. In both cases, the suspects were convicted on the basis of footprint evidence. William Habron was sentenced to life imprisonment and remained behind bars until the real killer of PC Cock confessed, whereas Henry and Francis Tidbury were convicted of the murder of the two police officers and hanged.

A new era of crime scene examination

The first formal CSI manual was published in 1893 by Austrian Professor of Criminal Law Hans Gross. His groundbreaking book, Criminal Investigation: A Practical Handbook, was translated into English in 1906. Together with French criminologist Edmond Locard, Gross laid the foundations for modern crime scene investigation. The handbook offered new tools, protocols and practices, which transformed the location where a murder took place, into a ‘crime scene’. His practical manual included advice on the collection and preservation of physical evidence, the importance of trace evidence such as blood other bodily fluids, and key detective skills like observation and deduction. Gross demonstrated how to sketch a crime scene onto squared paper to plot the exact location of items and the relationship between them, and how to secure crime scene objects. He even made a checklist of equipment for investigators to take to the scene, including blotting paper, a tape measure, plaster of Paris for taking footprints, and a bar of soap for making impressions of keys or teeth.

By the end of the nineteenth century, developments in CSI began to gather pace in Britain. New techniques included taking mugshots, fingerprinting and crime scene photography. These innovative technologies paved the way for the significant advances in forensic science of the early decades of the twentieth century, when crime scene investigation was formalised. The ‘murder bag’ (pictured at the top) was introduced in 1924, the first version including a large magnifying glass, rubber gloves, a plastic apron and disinfectant. The following decade saw the emergence of forensic laboratories in England, and the first training course for detectives was established in 1935, the curriculum of which included CSI.

If you would like to know more about the history of CSI, including my doctoral research into the subject, you can upgrade to view my paid posts.