Murder tends to follow me around and, although I hadn’t been aware of it when I was growing up, this particularly dramatic death took place just near my childhood home, a century before I lived there. In 1876, a police officer was killed on his beat in a leafy suburb of Manchester. Within thirty minutes of PC Cock’s murder, the prime suspects had been arrested, one of whom was later sentenced to death. Three years later, an astonishing revelation challenged the evidence in this intriguing case, leading to one of the nineteenth century’s most sensational miscarriages of justice.

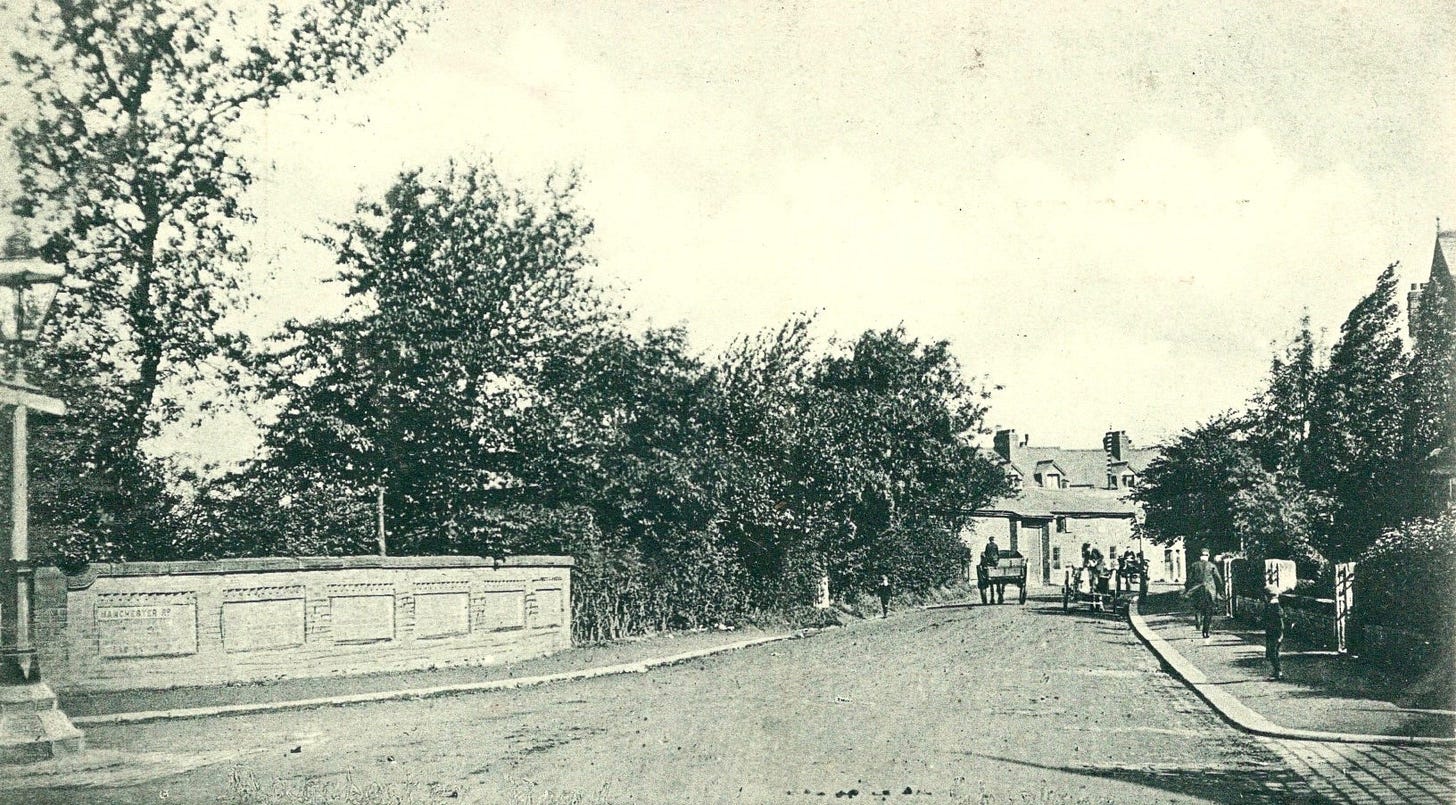

At midnight on 1 August, PC Nicholas Cock, aged 21, was nearing the end of his beat in Chorlton-cum-Hardy. As he approached the junction of three main roads, he was overtaken by a law student on his way home after a night out. The men stopped to chat and were soon joined by another officer. After a few minutes, they all went their separate ways. The student had walked some 150 yards away from the intersection, when he heard two shots ring out in the darkness, followed by screams of ‘Murder!’ He ran back to find PC Cock lying in the road, blood streaming from a gunshot wound in his chest. His colleague, PC Beanland, hailed two passing night soil carts and they carried the injured officer to a nearby doctor’s surgery. At 1.10 am, despite the doctor’s best efforts, Nicholas died. But by then, the search for his killer had already begun.

A swift investigation

PC Cock was attached to the Manchester Division of the Lancashire Constabulary. His superior officer was Superintendent James Bent (I am not making this up!), an experienced and tenacious law enforcer. During his thirty years on the force, Superintendent Bent had infiltrated gaming swindles at racecourses, exposed swindlers and con artists, and apprehended thieves, pickpockets and murderers. A determined man, his favourite adage was: ‘Always believe everybody guilty until you prove them innocent.’ It was on this basis that he proceeded straight to the home of his key suspects, before PC Cock had breathed his last.

When Superintendent Bent received news of the shooting just after midnight, he knew immediately who the culprits were: ‘I suspected these men from the first.’ He went straight to Firs Farm, where three Irish brothers worked as labourers. John, Frank and William Habron, aged 24, 22 and 19 respectively, had regularly crossed paths with PC Cock, resulting in their summons to court for drunkenness several times. The brothers were well-known in Chorlton-cum-Hardy for drinking and making threats to the young, and rather zealous, police officer. On the day of the murder, John Habron had received a fine for drunken and disorderly behaviour, for which he blamed Cock. After PC Cock’s death, Superintendent Bent joined his officers at the outhouse where the brothers were sleeping.

When Bent entered the premises, he found all three brothers in bed, where they claimed to have been all evening. Yet, William’s boots were wet and muddy, pointing to a recent walk through the fields. Highly suspicious, Bent arrested all three. The police then searched the outhouse and found some percussion caps in William’s waistcoat pocket. Superintendent Bent returned to the crime scene and found ‘the most perfect footprint’ in the gravel path leading to the farm from the junction. He sent to the police station for William’s boots and confirmed that they matched. He took no cast of the prints, but simply made new impressions with the boots alongside them. Although, by this time, it had started to rain, he managed to preserve them with a cardboard box. Later, he also found a bullet in the garden wall, in front of which PC Cock had been standing when he was shot. It matched the one extracted from the officer’s spine. The bullet and the percussion caps, along with the incriminating footprints formed the chain of evidence in the case.

Justice is served?

The trial of John and William Habron opened at the Manchester Assizes on 27 November 1876. Apart from the key evidence of the footprint and the bullet, witnesses for the prosecution testified to the ongoing tensions between the brothers and the deceased police officer. Also, intersestingly, there was some ambiguity from two men who were at the scene when PC Cock was shot. PC Beanland, described seeing a ‘mystery man’, who turned the corner of the junction under the gaslight, whilst he was talking to the others: he was dressed in dark clothing, of medium stature and walked ‘in an ordinary way’. The man was aged about 22 and had a fresh complexion. The law student also saw the man, but he said that he looked older and walked ‘in a faltering, loose kind of way.’ This was not considered important at the time, but would certainly be later. Despite the difference in opinion, William Habron was identified as the man they had seen that night. A further key eyewitness claimed that William Habron had entered his ironmonger’s shop in the city centre, possibly on the day of the murder, to enquire about cartridges for a firearm.

John Habron was acquitted, but his younger brother William was found guilty of Nicholas Cock’s murder and was sentenced to death. As a campaign was launched to spare William from the gallows, debate raged in the local press about the prisoner’s guilt. One of the jurors wrote a letter to the editor of the Manchester Courier, in which he revealed that Habron had been convicted on the evidence of the boot print. However, it is also likely that anti-Irish prejudice, which was rife in Victorian Manchester, had a direct and negative impact on the outcome of the trial. However, there was some clemency for the 19-year-old, and his death sentence was eventually commuted to life imprisonment. Still protesting his innocence, William was transferred to Millbank Prison, where he was soon forgotten.

An unexpected twist

Two years later, on 18 November 1878, a man named John Ward was tried at the Old Bailey for burglary and the attempted murder of a police officer at Blackheath. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and, while he was in jail, the police discovered that his true identity was Charles Peace, a notorious burglar from Sheffield, who was wanted for the murder of his lover’s husband two years earlier. In February 1879, he was tried for murder in Leeds, and sentenced to death. Whilst awaiting his execution, Peace made a startling confession; he described how he had killed PC Nicholas Cock during a burlary.

Despite Charlie Peace’s confession, William Habron remained in prison until another campaign secured his release. Almost three years after the murder of PC Cock, Habron was finally granted his freedom. Although he received compensation, William Habron never received an apology for his wrongful conviction as Constable Cock’s killer.

In my next newsletter for paid subscribers, I’ll be sharing Charlie Peace’s story, and his version of PC Cock’s murder.

Also, you can read the full story of this fascinating real-life crime case in Who Killed Constable Cock?