Welcome to the first post of my ‘new’ newsletter, The Detective’s Notebook, I thought I’d kick off with an introduction to my sleuthing work so far on Victorian and Edwardian detectives.

I became interested in police detectives when I was researching my family history in my home city of Manchester. My great-grandparents lived in Ancoats – they had migrated there from Italy in the 1890s. Whilst I was studying their community, I came across a prominent police detective, Jerome Caminada, who also had Italian roots and was fighting crime in the city’s nefarious underworld at the same time as my ancestors were living there. I ended up writing his biography, The Real Sherlock Holmes. But I wanted to learn more about the historical crime investigators like Caminada, and soon discovered that no one had really researched them – most historians focus on Scotland Yard. I decided to have a go, and I embarked on a journey into the shadowy world of the detectives.

The full title of my PhD thesis (I can never remember it without looking it up!) is: The Science of Sleuthing: The Evolution of Detective Practice in English Regional Cities, 1836-1914. For this study, I researched the activities of police detectives in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham, as there had been no studies on the pioneering investigators based in these cities. This is what I discovered…

My top ten takeaways:

1. Scotland Yard was not the first detective department in England – although I have lived in the south of England for many years, I am still a northerner at heart, and I felt rather smug to discover that the Manchester City Police created a detective office in 1839, a whole three years before the Met. There were no surviving records from this period, but I was able to find an advert in the city’s press for a vacancy for an ‘indoor superintendent’ to lead the detective department and ‘take measures necessary for the detection and securing of offenders’ (The Manchester Courier, 18 May 1839). A later notice confirmed that the appointment had been made.

2. Detectives relied on traditional investigative skills – my research confirmed that borough police detectives mostly used tried-and-tested methods of crime detection, such as information gathering, surveillance and local knowledge, to track and arrest suspects for a wide range of offences from theft to murder. Also, these practices were discussed and modified by the watch committee, who were responsible for management of the police, especially in reference to the modus operandi of Scotland Yard detectives, of whom they were generally disapproving!

3. Communication was very basic – despite telegraphic systems being installed in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham in the 1860s, the detectives preferred to stick to using the ‘route form’ (a written message passed on foot) as their main means of communication, as they thought it was quicker! (Before the telegraph was introduced into the police stations, they had to go to the public office or a fire station to send telegraphic messages.) By the end of the nineteenth century, despite the advances in communication technology, they were still using the old-fashioned route form rather than the telegraph.

4. Early detectives relied on their memory – I found evidence of borough detectives making regular prison visits to improve their knowledge of habitual offenders and to develop memory skills. However, this didn’t take place in Liverpool, as the head constable said it wasn’t necessary! Other informal training activities included shadowing a more senior investigator, spending time in court and even visiting other cities to share knowledge and identify potential offenders. Formal training and education were not introduced into regional forces until the early twentieth century.

5. Detective departments created their own criminal databases – my study revealed that, after the Habitual Criminals Register was introduced in 1869 at Scotland Yard, borough detectives generally did not engage with it, due to a sense of rivalry and pride, in that they saw it as a failure to solve their own crimes. Instead, they compiled their own records, for instance, Birmingham Police had a tattoo register with hand-drawn images and Liverpool Police had an index of the female names in offenders’ families, such as their mother’s or wife’s, as detectives surmised that these were most likely to be used as aliases.

6. Cameras were used for photographing offenders – although cameras were introduced into borough police forces in the 1850s, they were mainly used to take mugshots for criminal records, rather than for photographing crime scenes, as this required outdoor cameras, which were too expensive. The high costs were due to most police forces having to outsource the taking of external photographs to professionals, with the exception of Birmingham Police who had a trained photographer in their ranks who undertook the role.

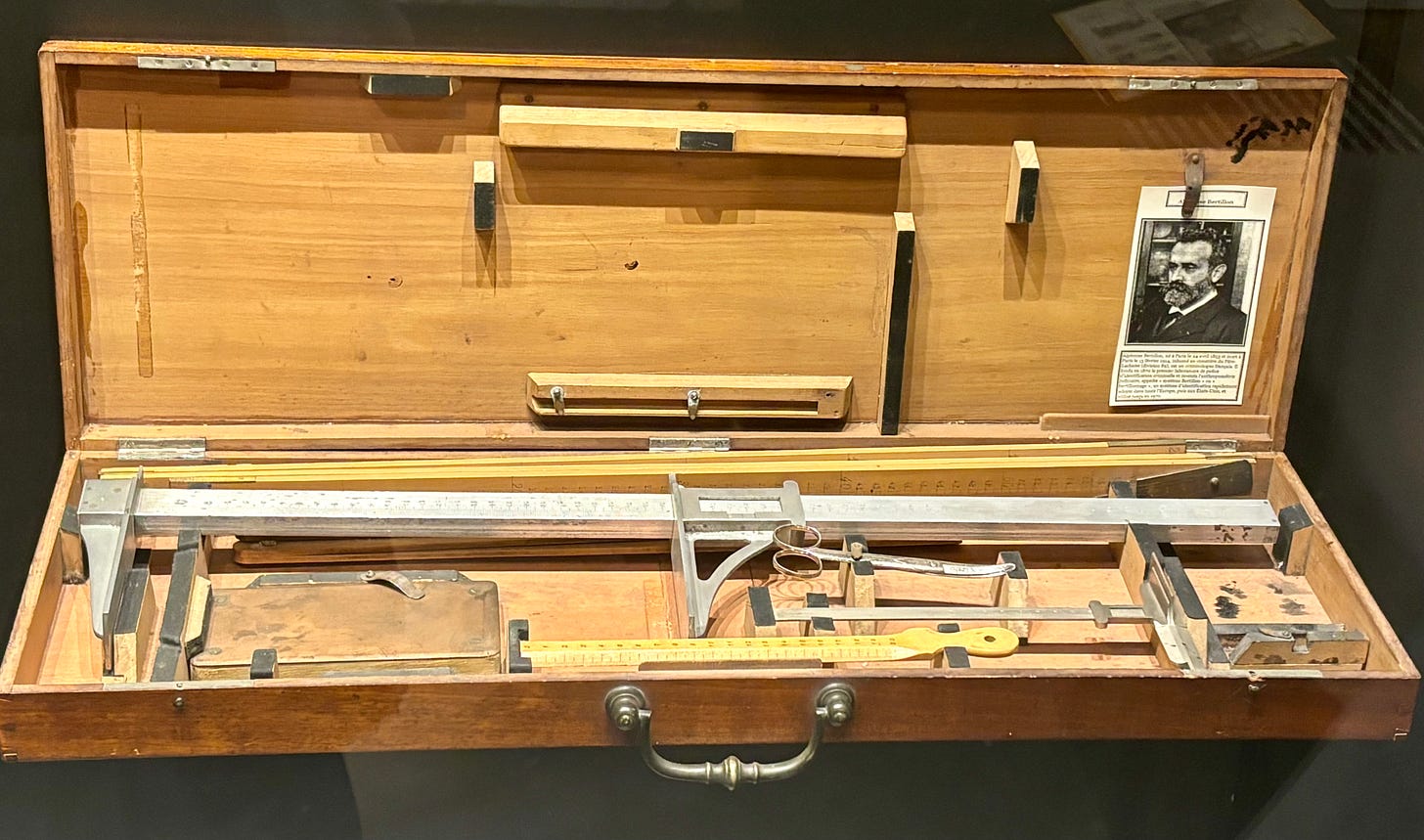

7. Regional detectives gradually adopted habitual offender ID methods – the development of offender identification was not standardised in regional detective policing, with some forces being slow to adopt new techniques. Some borough police forces, such as Manchester City Police, used Bertillon’s measuring system for repeat offenders, but it was soon superseded by fingerprinting in the early 1900s. The practice of taking fingerprints wasn’t widespread, however, until the mid-twentieth century, due to the cost of equipment and the need for specialist training.

8. Early detectives used CSI techniques in poison cases – the first example of crime scene examination I discovered was from Liverpool in 1860. There were no instruction manuals for police officers on CSI at this time. From the mid-nineteenth century, detectives collected, labelled and preserved evidence, and kept it the storeroom in the detective office, which was managed by a detective storekeeper. Liverpool City Police created their own evidence labelling system using the initials of the suspect when they were preparing samples for court.

9. Borough detectives sent evidence away for analysis – investigators used public and private analysts for chemical testing from the 1870s for a range of cases including arson, explosives and murder. They did not use these services systematically but selected them for specific investigations, usually based on cost. Individual detectives often conveyed the evidence to analysts, sometimes to London, for which they usually travelled by train, carrying the specimens in jars.

10. Detectives used crime scene sketches – scale plans, sketches and models of crime scene came into use in the judicial process from the 1840s. In my study I found that, from the 1880s, detectives contracted out crime scene drawings, plans and models for use in murder trials, as an aide-mémoire for the jury. They often included a cross to mark the location of the body or, like the one above, the position of the blood spatter. Later in the period, the sketches also had an investigative function, with the creation of timelines to examine the route a suspect may have taken or the position of witnesses.

Overall, my conclusion was that, although regional Victorian and Edwardian detectives were sometimes reluctant to adopt new technologies and national initiatives, they used a ‘blended’ approach and were far more professional, effective and innovative than historians had previously given them credit for. There were some extremely experienced and expert investigators who perhaps did not enjoy the same celebrity status as their famous counterparts from London, but who were nonetheless excellent sleuths. There is much more exciting research to be done in this fascinating field, which I’m looking forward to exploring with you through this newsletter.

The next entry in The Detective’s Notebook will be an examination of a notorious early nineteenth-century murder in London, which reveals the rather patchwork and rudimentary nature of pre-Victorian policing. But before that, later this week, in The Confidential Files (for paid subs), I’ll be sharing my top tips on how to investigate a murder!