Like Sherlock Holmes, real-life detective Jerome Caminada of the Manchester City Police was a master of disguise. Carrying his clothing in a large bag when travelling by train to other parts of the country, he donned different outfits for undercover work, even using false facial hair and wigs, passing himself off as a salesman, a warehouse worker and even a butcher. One case, in which being in disguise was particularly effective, was when he tackled the insidious quack doctors in his home city.

An insidious trade

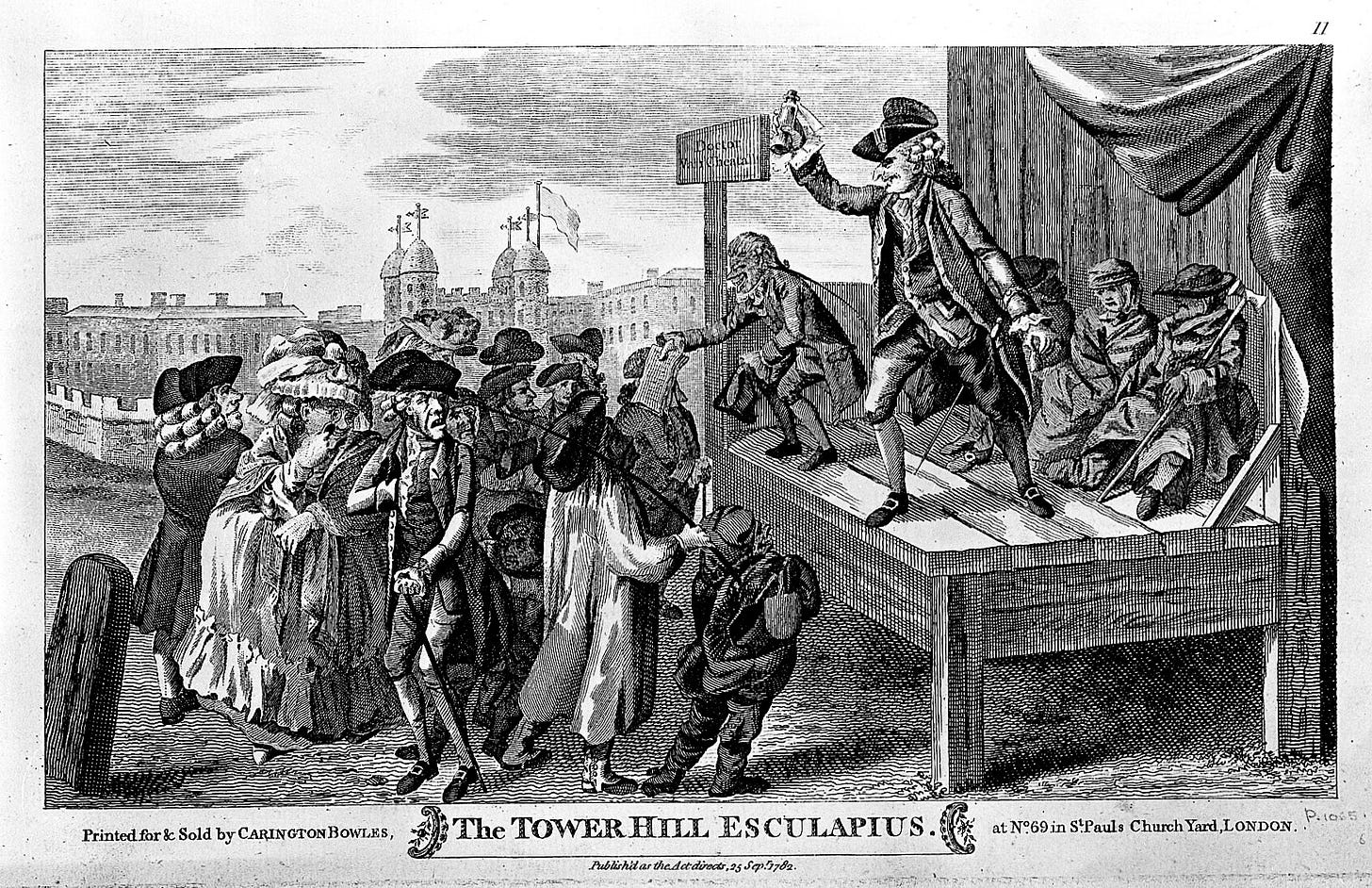

Urban life throughout Victorian England was precarious, but in Manchester it was downright deadly. Shoddy housing, a lack of clean water and poor sanitation posed major health hazards for many city-dwellers. Killer diseases, such as cholera, typhus and influenza swept through the tightly packed communities bringing illness and death to thousands in their wake. The death rates in Manchester, during the first half of the nineteenth century, were well above average and in 1842, two years before Jerome Caminada was born, the average life expectancy among working people was just eighteen years. It was not surprising, therefore, that people were anxious about their health, leading to the more wealthy residents moving out of the city centre to the leafy suburbs, leaving the most vulnerable at risk. However, regardless of their social status, the citizens of Victorian Manchester were in a near-constant state of panic, and ruthless fake doctors exploited the most susceptible members of the public.

Detective Caminada came across this phenomenon, for the first time, when he called into a pawnbroker’s shop on his way home from work to see a friend. Inside the shop, the manager and his assistant were poring over some prints on the counter, in the presence of a young man, who looked distinctly peaky – his body was shrunken, his face cadaverous, and his eyes were bright with fever. Ever suspicious, Caminada wondered if the man had stolen the prints from his employer, so he searched his room, where he was astounded to discover 153 medicine bottles – the desperate thief was in the grips of a quack doctor and had been stealing in order to fund his habit. His obsession had begun when he read a pamphlet in the street listing the most ‘horrible ailments’, which had then led him to the only hope of a cure: the health-giving elixir promoted through the handbill. The ‘medicine’ had had the opposite effect and his health had deteriorated, forcing him to return to the doctor for more supplies, and falling into debt in the process. Detective Caminada was so moved by the young man’s plight that he vowed to rid his city of such ‘rascality, rapacity and roguery’.

Quacks are, in truth, greater enemies to society than the garroter or burglar.

Throughout the following months, Jerome Caminada led his campaign against the quack doctors operating in Manchester, which led to many prosecutions, even as many as twelve in one week. To achieve this, he assumed the persona of numerous tradespeople, such as a solicitor’s clerk and a commercial agent, and feigned illnesses, including chest pains, deafness and sweaty palms. He made appointments with the doctors in their plush offices, attended consultations and purchased treatments, which he then had analysed. When the ingredients of the fake potions were exposed, he arrested the charlatans and prepared the cases for court. However, there was one very accomplished swindler who would prove more than a match for the wily detective.

The ultimate quack doctor

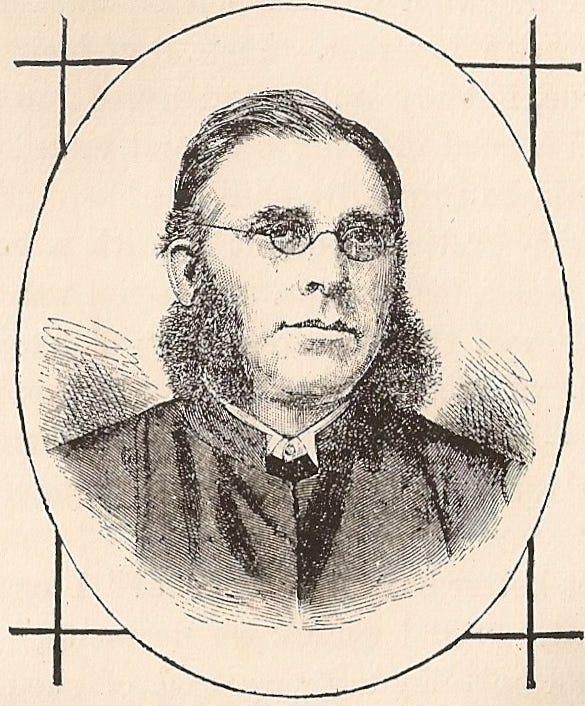

In 1877, Jerome Caminada spotted an advertisement for a new cure-all tonic, 'Food of Foods', in a local newspaper. He was immediately intrigued and decided to investigate. The Reverend Edward James Silverton was a Baptist minister from Nottingham, who had even built a church for his loyal congregation. His faithful flock, however, were unaware that their celebrated priest was a crook. The ruthless quack doctor claimed that his wondrous tonic could alleviate all manner of illnesses, and was especially efficacious in curing deafness. Detective Caminada conducted a lengthy correspondence with Silverton and when the dubious practitioner finally came to Manchester, he made an appointment for a consultation at the Free Trade Hall, which the minister had hired for his well-publicised lecture tour.

Dressed in shabby clothing and affecting a limp by putting on an old shoe, Caminada presented himself for his medical examination. Unfortunately, Reverend Silverton wasn’t available after all, and the detective was forced to consult with his assistant who, without even examining the ‘patient’s’ foot, diagnosed rheumatism and recommended a medicine for 35 shillings (about double the weekly wage of a labourer). On analysis, the miraculous ‘Food of Foods’ turned out to be a concoction of lentils, brown flour, bran and water. The detective acquired a summons for Silverton but unfortunately the case was later dropped by the public prosecutor, despite the number of individuals who came forward to share their stories of being duped by the expert conman.

The infamous Reverend Silverton remained at large, and continued his nefarious practices until his death, in 1895. However, Detective Caminada had another encounter with his quack trade, when he visited Silverton’s daughter, who had joined her father in business. On examination, she reported that Jerome’s hearing had gone in one ear, and was partially destroyed in the other. After she proposed a four-month treatment to restore his hearing, which would cost £29 6d., Caminada knew that she too was a fake.

This lady quack, a worthy descendant of her “wonderful-curing” papa, had not been tutored in vain.

Fortunately, as conditions improved during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the need for the nefarious ministrations of the quack doctors declined. However, there were many other ruthless con artists on the streets of Manchester, as well as a ready supply of gullible victims, to keep Detective Caminada busy.

You can read more about Detective Caminada’s adventures in my book, The Real Sherlock Holmes.