I grew up in Manchester and, when I started researching crime history, I was delighted to have the opportunity to delve into my home city’s colourful past.

In the nineteenth century Manchester was one of the most dangerous places to live, with grinding poverty and staggering crime rates. The Industrial Revolution had brought tremendous wealth for businesspeople and factory owners but, for thousands of others, life was tougher than ever and they were forced to resort to desperate measures to survive.

The towns of northwest England had been the centre of cotton production since the eighteenth century and by the 1790s, 70 per cent of the British cotton industry was located in Lancashire and Cheshire (it would reach 90 per cent by 1835). With its well-developed network of warehouses, manufacturing skills and early transport system of canals and then the railways, Manchester became the epicentre of trade and well deserved its nickname of ‘Cottonopolis’. During the early 1800s, the first industrialised city in the world experienced a massive population explosion as workers flooded in to find employment in the factories and mills. In 1801 the number of inhabitants was 76,788 but 50 years later, it had more than quadrupled to 316,213. It was estimated that in 1841 alone, some 40,000 migrants were arriving every week by horse-drawn coach and train. Most of these newcomers were forced to live in some of the worst accommodation in the country and endured atrocious conditions at work.

The great divide

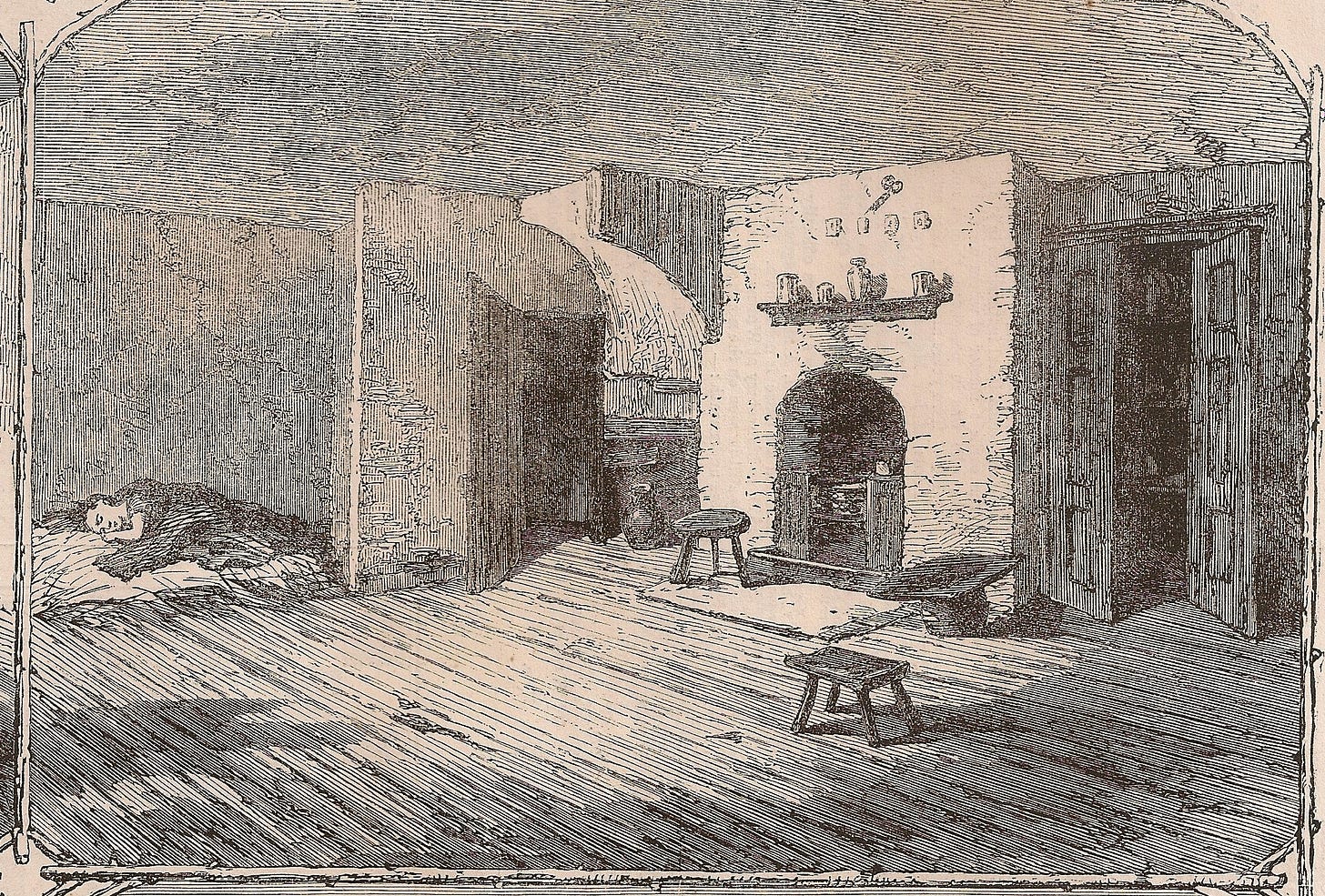

As they accumulated wealth, the business and factory owners moved out into the leafy suburbs, leaving their work force behind to struggle in the dirty streets of the smoke-blackened commercial centre. Friedrich Engels summed up the harsh reality in The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844: ‘Everywhere barbarous indifference, hard egotism on one hand, and nameless misery on the other’. At the time of his study, there were some 400,000 inhabitants in the workers’ quarters, 20,000 of whom lived underground in the infamous cellar dwellings. The unpaved streets were filthy, with stagnant pools of human and animal waste. Large families were crammed into tiny back-to-back tenements with no running water and poor ventilation. The living conditions were almost unbearable, with minimal amenities and barely a stick of furniture. It is not surprising therefore that many people turned to crime in their daily struggle for survival.

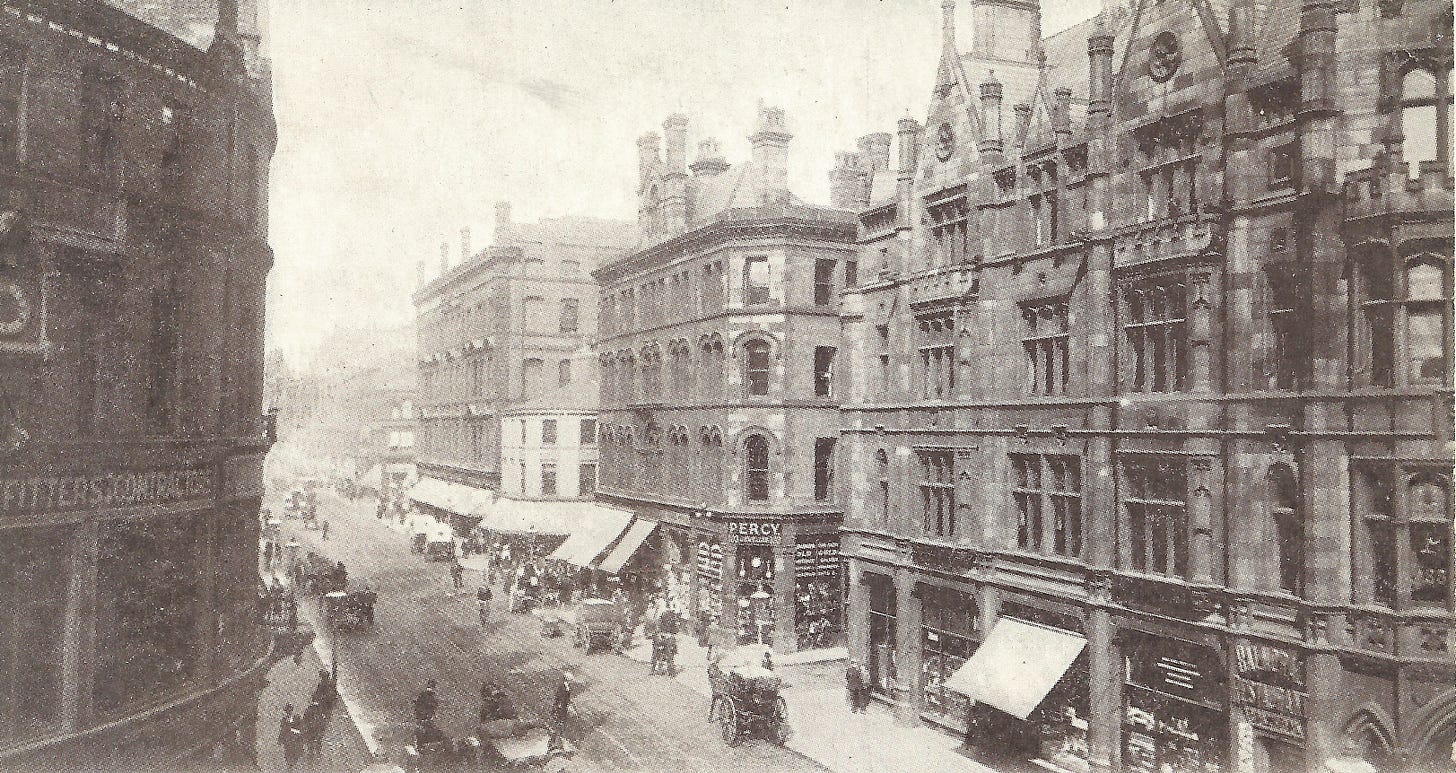

The rookeries of central Manchester were notorious for crime of all kinds, from pickpocketing and forging, to violent assault and even garrotting. One of the worst slums was around the central thoroughfare of Deansgate. Dubbed ‘Devil’s Gate’ by a contemporary newspaper reporter. Behind the shops and offices of this busy commercial district, were some of the seediest streets in Victorian England, with beerhouses and brothels on every corner.

Street crime

Visitors to Manchester ran grave risks if they wandered into this insalubrious district and they were lucky to escape unscathed. Along the pavements were con artists and swindlers, who played out their well-rehearsed tricks for cash. One common ruse was to use soap to create frothing at the mouth and then to fall on the floor writhing, as if having a fit, in the hope that someone would throw a coin in pity. Another was the ‘ring-dropping scam’, where a ‘sharp’ (con artist) dropped a fake ring on the ground and their accomplice, a seemingly innocent passerby, would pick it up and comment on its value. The trick succeeded when a genuine bystander offered the first swindler an exorbitant price for the ‘precious’ jewellery.

Children were hired to beg and ‘distressed’ women lured gentlemen into the shadows to help them, only to be robbed and beaten by a gang of bullies. Professional beggars included out-of-work colliers and soldiers returning from war, none of whom had ever been down a mine or visited a battlefield, often faking injuries to plead their cause more convincingly. The black market flourished in the slums, with ‘fences’ (dealers in stolen goods) employing a variety of charades to shift their merchandise, such as sham sailors who had returned from high adventures on the seas with ‘treasure’ rescued from shipwrecks. Everywhere there were tradespeople, or ‘land sharks’ plying their trade, offering cheap clothing, household goods and fake jewellery. If visitors managed to avoid the swindlers and cadgers, then they were likely to have their money and valuables lifted by the pickpockets and sneak thieves. ‘Swell mobsmen’ were experts in theft. Well-dressed and appearing respectable, they engaged an unsuspecting victim, or ‘mark’, in conversation, or found an excuse to come alongside them. Then, whilst their attention was turned, they would slip a steady hand into a waistcoat or breast pocket to relieve them of their wallet or purse.

High alcohol consumption added to the problems on the streets, as workers sought to ease their relentless existence in the numerous beerhouses and gin palaces. Beer sellers sold beer from barrels in their front rooms, turning them into makeshift bars with a rough counter and small wooden tables (including my 3 x great-grandfather who also ran a brothel!). In 1843, there were 502 public houses and 781 beerhouses in the city. By the 1860s, there were as many as 2,000 in total. Drinking was often accompanied by music and dancing, and in the more disreputable houses, there would be prize fighting, dog fighting and illegal gambling.

Official police returns confirmed the high incidence of crime. In 1866, there were some 13,000 arrests, half of which were for drink-related crimes. Theft and pickpocketing were the most common offences. One twelfth of arrests were for prostitution and the police estimated that there were 325 brothels, housing some 800 sex workers.

By 1870, the number of arrests had doubled. Indictable offences included assault, breach of the peace, drunkenness, stealing and prostitution. The crime rate per capita was 1.86, which was four times higher than that in London during the same period, confirming Manchester as the ‘crime capital’ of Victorian England. As only five per cent of arrests resulted in conviction, the Manchester City Police Force had its work cut out.

Law and order

The new police force was established in 1839, following the creation of the Manchester Borough Watch Committee. In the early 1840s the organised, and more professional, police force was comprised of just 398 police officers, who served a population of 242,000. The majority of new recruits were young and inexperienced. As the force developed, it was separated into five divisions with the headquarters, along with the detective department, at the new town hall, built in 1877. By this time, the number of police officers had increased to more than 700.

The situation in Manchester slowly improved due to better living conditions, the evolution of social legislation, and more effective policing. Furthermore, from mid-century onwards, many of the slums were cleared to make way for the construction of the railway stations, forcing the inhabitants away from the ghettoes in the city centre and dispersing the criminal element.

Now, when walking around the city, it is hard to imagine how terrible the streets were over a century ago, but there are some traces of its colourful past; some old pubs remain as well as the labyrinthine passages where the suspicious characters used to lurk..