In Oscar Wilde’s legendary poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, he described the fate of trooper Charles Wooldridge, who was executed for the murder of his wife. As was customary, the felon was buried in the grounds of the prison, and quick lime was added to hasten the decomposition of his body.

For where a grave had opened wide,

There was no grave at all:

Only a stretch of mud and sand

By the hideous prison-wall,

And a little heap of burning lime,

That the man should have his pall.

Quick lime was often used for the burials of those hanged in prisons during the nineteenth century, but it also had another, even more sinister, purpose: to dispose of a body in an attempt to remove the distinguishing feature of a corpse as quickly as possible. I am in no way a scientist, but I am intrigued by the application of science in historical crime, and I find it fascinating that some murderers used this method to try to remove traces of human remains, after committing their fatal act.

Criminal uses

On 17 August 1849, whilst investigating a missing person case, two police officers discovered the body of a man under some flagstones in the kitchen in a house in Bermondsey. Noticing a damp patch on the stone floor, PC Henry Barnes and his colleague removed the flags and dug into the wet mortar, until they came across a man’s toe and then his loins. The man, who was naked, was facing downwards, with his legs drawn up behind him and tied with a clothes-line. His head was buried slightly lower in the ground, embedded in slack lime which, according to the press, ‘had commenced its work of destruction…the flesh in several places being eaten away’. The quick lime, which had been used in the belief that it would hasten the decomposition, was washed from the body before the post-mortem and, although his face was partly decomposed, the victim was identified as Patrick O’Connor by his set of false teeth. When the police later excavated his ‘grave’, they discovered a layer of lime beneath where his body had lain. At the trial of O’Connor’s murderers, Maria and Frederick Manning, the supplier of the lime stated that it would have accelerated the decomposition of his body.

Over sixty years later, quick lime was still used for this nefarious purpose, most notably in the murder of music hall artiste Belle Elmore, who disappeared from her home in Holloway, North London, on 31 January 1910. Detective Chief Inspector Walter Dew, from Scotland Yard, was called upon to investigate the case and, after several searches of the house she shared with her husband Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen, the senior police officer finally found human remains under the coal cellar floor.

‘We found only masses of human flesh. The head was missing. No bones were ever discovered. Identification seemed impossible’

What little was left of the body, which had been under the cellar floor for several months, had been covered in quick lime. The preserved remains were linked to the missing Belle Elmore by an abdominal scar. Furthermore, when the tissues were tested, it was revealed that she had likely been poisoned with hyoscine. Dr Crippen was convicted of her murder and executed. At his trial, celebrated anatomist, Dr Joseph Pepper, also stated that the lime would have aided decomposition. Although a century later, these findings are questionable, nevertheless the action of the quick lime preserved the evidence that sealed the fate of Belle’s killer, and Dr Crippen did not get away with murder.

I mixed crime history and chemistry to investigate this practice further and to find out how effective it actually was.

The science behind the crime

Limestone was commonly used in construction and was readily available in the nineteenth century, especially in places like Bermondsey, where it was also used in the tanning pits. In one of the oldest known chemical processes, when limestone (calcium carbonate) is heated, it breaks down into calcium oxide and carbon dioxide, which is called ‘thermal decomposition’. The calcium oxide is the ‘quick lime’. This highly-caustic alkali burns yellow when hot and is white when cooled. It is an unstable compound and reacts with the carbon dioxide in the air to create heat energy, known as ‘limelight’. When quick (also known as ‘unslaked’) lime is mixed with water, it does have an initial burning effect, but it then preserves, rather than destroys tissue, and actually slows down putrefaction by drying out the soft flesh.

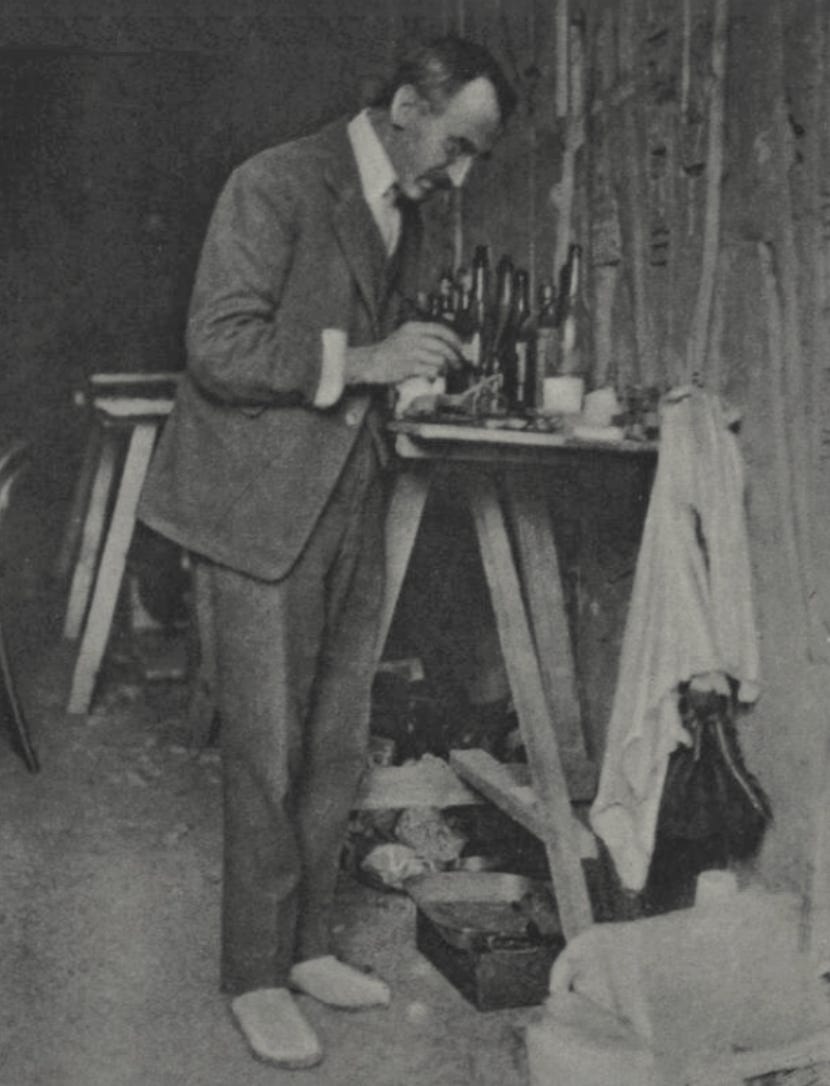

British analytical chemist and noted Egyptologist – he worked with Howard Carter on the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun – Alfred Lucas was the first person to examine the effects of quick lime on cadavers by burying dead pigeons in the ground. After six months, the bird buried with quick lime, and the one interred with quick lime and water, both remained preserved, with no signs of putrefaction. Therefore, if quick lime is applied to a corpse, which is then buried in damp earth, the moisture hydrates the lime and the body gradually becomes mummified.

In 2011, further research was undertaken in Belgium into cadaver decomposition, in an experiment by forensic scientists using the carcasses of six pigs; two were buried in soil without lime, two with quick (dry) lime and another pair with hydrated lime. Following the field work, additional experiments were made in laboratories at the University of Bradford. The results were that both the hydrated and quick lime slowed down the decomposition of the carcasses for six months (it also apparently decreases insect activity!). However, quick lime can mask the smells of decay, which I guess might have been useful in historical homicide cases.

In conclusion, the efficacy of quick lime for the clandestine disposal of a body is a myth, as it would eventually dry it out. I do like an urban myth, particularly when it relates to the history of crime!

It is a fascinating article and insightful. I have even heard many people perpetuate this myth.