Warning: depictions of historical domestic abuse

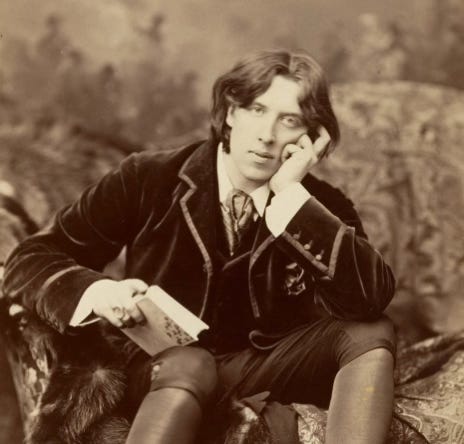

Ever since I came across his eye-catching gravestone in Père Lachaise cemetery for the first time, while I was a student in Paris almost forty years ago, I have been fascinated by Oscar Wilde. The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of my favourite Victorian novels and, in real life, the writer also suffered a tragic downfall after he was convicted of gross indecency in 1895, due to his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, the son of the Marquess of Queensbury.

After spending time in Pentonville and Wandsworth Prisons, Oscar Wilde was transferred to Reading. He arrived at the railway station on a cold winter’s morning in November 1895, and later recalled:

For half an hour I stood there in the grey November rain surrounded by a jeering mob.

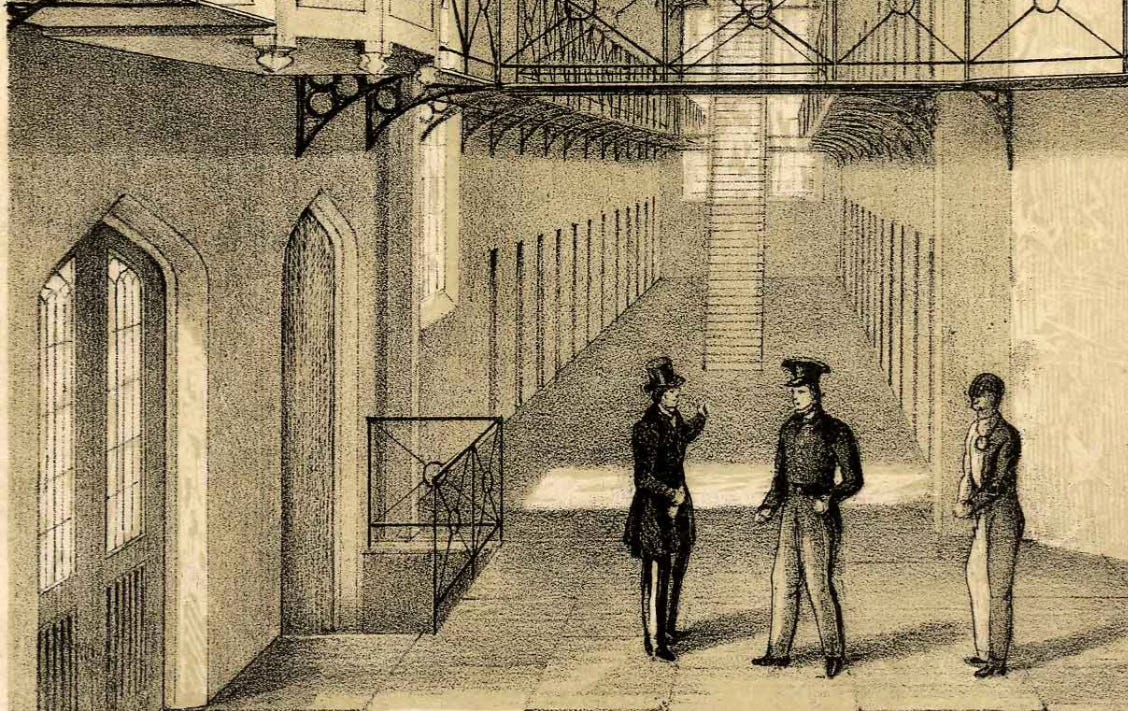

It was an inauspicious start. At the prison, Wilde was allocated to C-ward, which was for convicted prisoners. As was customary, his cell number C.3.3. became his name throughout his stay at the gaol. The cell itself was 13 feet long by 7 feet wide, with a stool, table, shelves and a drawer. There was a hammock made of coconut fibre for sleeping and a chamber pot – originally the cells had cisterns but they had been replaced by much more primitive sanitation to make life even harder for the late-Victorian prisoners. On arrival, Oscar had his hair cut and exchanged his elegant clothing for the standard grey prison uniform with arrows on it and the dreaded Scottish cap, which prevented prisoners from making eye contact with each other.

Prisoner C.3.3. would remain at HMP Reading for almost two years and, during his incarceration there, he would witness an execution which he would later immortalise in his legendary ballad.

A tragic act

On 7 July 1896, trooper Charles Wooldridge was executed at Reading Prison for the murder of his wife, Laura Ellen Wooldridge.

When they found him with the dead,

The poor dead woman whom he loved,

And murdered in her bed.

Described in the local press as ‘a young lady of a somewhat prepossessing appearance, and most respectably connected’, Laura Ellen Wooldridge née Glendell was born on 21 June 1872, in Bath. Her parents were Alfred George and Jane Glendell. Ellen had a brother, Alfred Edward, who was two years older. The family lived in the city centre, where their father was a successful woollen draper, selling wholesale fabrics for clothing manufacturing. In 1876, when Ellen was almost four years old, her mother died of phthisis, a wasting disease often attributed to tuberculosis. By this time, the Glendells had moved out to the leafy suburbs of Prior Park Gardens. Four years later, Ellen’s father remarried, and he and her stepmother had three more daughters and two sons. To support his growing family, Alfred found work as a commercial traveller, which would have meant time spent away from the busy household. Ellen and her older brother Alfred junior attended school. At the beginning of the 1890s, when Ellen reached eighteen, she went to work as a draper’s assistant back in the city centre. In 1893, she moved to Windsor, where she met Charles Thomas Wooldridge, who was a trooper in the Royal Horse Guards. They were married in Kentish Town on 9 December 1894.

A complex relationship

Charles Thomas Wooldridge was born in 1864, in East Garston, Berkshire. A labourer’s son, he began work as a plough boy, together with his younger brother, Albert. By 1891, Charles had joined the Royal Horse Guards and was stationed in Farnborough, Hampshire. Shortly after their wedding, Wooldridge was transferred to guard duty at Windsor Castle but, as he had not sought permission to marry from his commanding officer, the marriage was not sanctioned by the army, and the couple were forced to live apart. Ellen rented lodgings at 21 Alma Terrace, Clewer, Windsor, and worked as an assistant at Eton Post Office. The postmistress later described her as ‘intelligent, courteous, and obliging, and punctual’. Ellen spent time training in telegraphy in Reading, and was liked by her customers.

Whilst Nell, as she was now known, was living in Windsor, Charles had been transferred to duty at Buckingham Palace and was stationed at Regent's Park Barracks. He visited his wife two or three times a week, and this arrangement continued for the following year but, at the beginning of 1896, relations between the couple became strained.

Alice Cox, who was Charles’ cousin, moved in with Nell in January. She described Nell as ‘an obstinate woman’ and claimed that she used her maiden name to cover up her marriage. There were rumours of an illicit affair, but Alice conceded that she had seen no evidence of this while they lived together. Only one man had visited Nell, apart from her husband, and this was Robert Harvey, also a trooper, who had come to the house once. He had remained in the sitting room with Nell, and had left early. As time wore on, Charles Wooldridge became increasingly jealous and suspicious of his wife.

A crime of passion

On 16 March 1896, Charles was visiting Nell, when a terrible row broke out between the couple, after which she emerged with black eyes and a broken nose. Seemingly repentant, Charles returned two weeks later, on 29 March, with a signed document stating that he would never touch her again. Nell agreed to see him and Charles entered the house. Alice went upstairs leaving them alone together, but it wasn’t long before she heard a scream. By the time Alice had dashed downstairs, Nell had been found lying in the road by a neighbour. Her throat had been cut. (She wasn’t ‘murdered in her bed’, as recounted in the ballad).

When Charles Wooldridge handed himself in shortly afterwards, he confessed to his wife’s murder and told the police that ‘she has been carrying on a fine game’. At the inquest, the coroner concluded that the murder had taken place because of ‘some misunderstanding between Wooldridge and the deceased and it looked like a case of jealousy’ (Berkshire Chronicle).

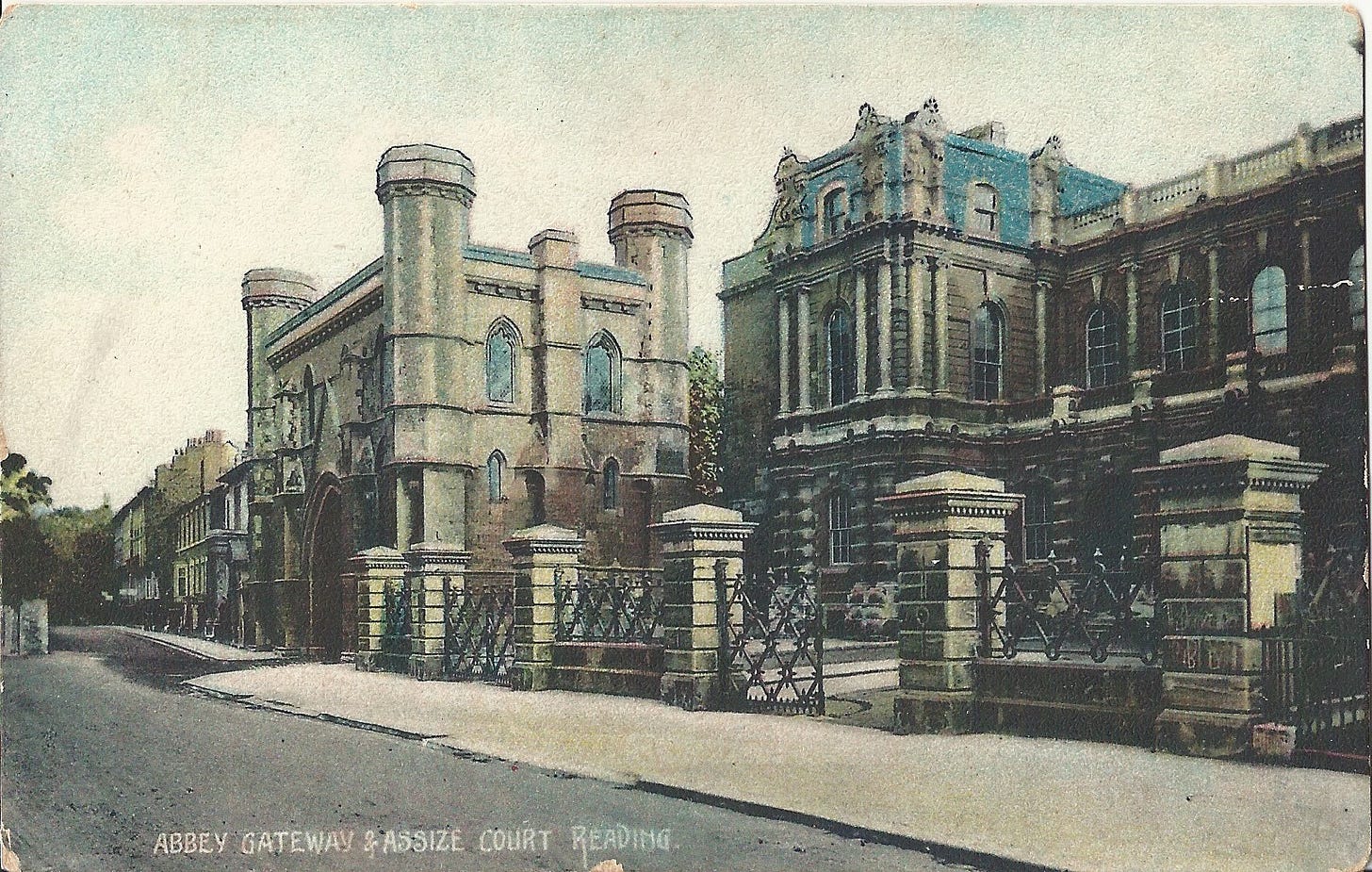

Charles Wooldridge's trial took place at the Berkshire Assizes in Reading on 18 June 1896. The trooper’s defence argued that he was a passionate man, who had loved his wife and had been angered by her change of attitude towards him, as well as rumours of ‘an intrigue’. In his summing up, Mr Justice Hawkins concluded:

If a woman expressed her wish to have nothing to do with her husband, that was no justification why the husband should commit murder.

The jury returned a guilty verdict, with a recommendation to mercy due to the defendant having been provoked, but no mercy was forthcoming and Charles Wooldridge went to the gallows.

A moving ballad

Wilde remained at Reading Prison until his release in May 1897, after which he fled to France. The following year, he published The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a poignant and wistful poem that laments the capacity for humans to destroy the things they hold the dearest:

I only knew what hunted thought

Quickened his step, and why

He looked upon the garish day

With such a wistful eye;

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die.

Wilde died in Paris in 1900, at the age of 46, without ever returning to England.

I visited Reading Prison for the first time in 2013, before its closure. I wasn’t able to go into Oscar’s cell as it was occupied, but the prison warders told me of a strange smell of tobacco which lingered outside the cell at night, which they said was the ghost of Trooper Wooldridge! Three years later, I was finally able to visit the cell of C.3.3. when I went back to the prison (now decommissioned) during an art exhibition.