The exploits of a Bow Street Runner

Bank thieves, illegal gamblers, highway robbers and Frenchmen on the run

I’ve been enjoying my research into pre-Victorian detective policing, such as in the Ratcliffe Highway murder and I’ve found it particularly interesting to discover that individual early detectives moved around the country solving crimes. One such is Stephen Lavender, who was in the Bow Street Runners and then relocated to Manchester, where he became deputy constable. His story conveniently fills in some of the gaps in my work in this area, as he was a colleague of Henry Goddard in London, who was also in the Runners, and then he succeeded thief-taker-turned-police officer Joseph Nadin in Manchester, both of whom I’ve studied and written about – it’s great to find another key piece of my police history jigsaw puzzle!

As, unlike Henry Goddard, Stephen did not publish any memoirs, it has been more difficult to find out about him and his sleuthing work but this is what I’ve uncovered so far…

Stephen Lavender was born in 1788, and lived in Bedford Street, north of the Strand and not far from Covent Garden, with his parents, Edward and Mary Ann. His father was a clerk at the Bow Street Police Office, where he sometimes engaged in investigative work. As often happens in policing families, at the age of nineteen, Stephen followed in Edward’s footsteps and joined the Bow Street force, likely starting in the foot patrol. Interestingly, his older brother, John Nelson Lavender, also worked as a police officer in Westminster. Two years after his enlistment, Stephen was appointed to the ranks of the famous Runners. His early adventures as an investigator offers a fascinating glimpse into the detective work of the Bow Street Runners, which involved travelling to different towns outside London to tackle a wide range of crimes, such as in Winchester.

A year after Stephen’s promotion, on Boxing Day 1810 a banker in Winchester left his premises at 10 pm, after ensuring that it was securely locked. The next morning, he discovered that the private bank, which was known as Waller & Co., (it’s now part of the NatWest Group), had been broken into via a hole the thieves had made under one of the windows. Money and notes had been stolen to the value of £1,000 (almost £70,000 today) including £110 in bank notes, which Mr Waller was confident he could identify. The banker enlisted Stephen Lavender to investigate, and he arrested the felons just three days later (there are no details in the newspaper reports on how he tracked them down so quickly). In a box in one of the suspect’s rooms, he found a £100 bank note, which had been deposited in the bank by the mayor and another that was identified by the local vicar. Richard Edsall and Samuel Bennett were tried at the Winchester Assizes. Samuel was acquitted, but Richard faced a death penalty – he was later reprieved. Stephen Lavender would have been well rewarded for his success.

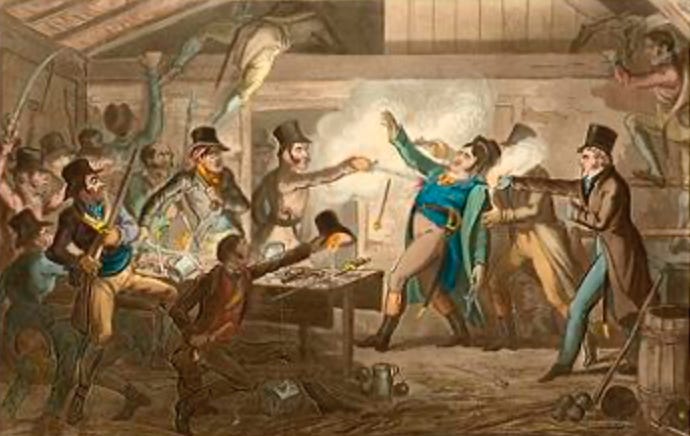

Over the next decade, Lavender worked tirelessly on many investigations. Together with his colleagues from the Runners, he infiltrated an illegal gambling club in the heart of London, near St James’s Palace, for which the officers broke into the house through a hole in the wall, as the door was too strong to penetrate even with iron bars and sledge hammers. Inside they found a large mahogany table with drawers in which they discovered dice boxes. When two ‘genteelly dressed’ men came into the room, Stephen arrested them.

On another occasion the indefatigable investigator tracked down several French officers who had been trying to make an escape (they were likely to have been prisoners from the Napoleonic Wars, of which there were over 100,000 in Britain). Acting on information received, Lavender and his associates staked out a covered cart in Thame, Oxfordshire, where the officers were hiding, the driver of which was a well-known smuggler. A boy who was accompanying them told the Runners that their escape had been impeded by local people having been offered a guinea for every Frenchman detected, which was presumably how the detectives had received the intelligence. Following this arrest, Stephen travelled throughout Kent searching for other escapees, and he discovered six more French officers being smuggled out in covered carts.

In 1812, Stephen was on the road again, this time to Spithead on the Solent, where he intercepted a casement of illicit firearms which were being transported from London to America. He also apprehended a known highway robber who had held up a stage coach on the road from Hertford to London. In 1813, Lavender provided evidence in the murder trial of Philip Nicholson in Maidstone, who had admitted to killing his employer and his wife. After the felon’s confession, the officer had searched his room and found a bloodstained shirt and some stockings which he produced in court. Nicholson was convicted and executed, and his body was sent for dissection. By 1819, Stephen Lavender had become so renowned as a detective that when the Duke of Gloucester was robbed of some money during a visit to Cheltenham to take the waters, he immediately sent for him to investigate.

Two years later, in 1821, Stephen Lavender resigned from the Bow Street Runners and was appointed deputy constable of Manchester where, despite his additional responsibilities, he continued to investigate crime, including several homicide cases.

Whilst scouring old newspapers for examples of Stephen Lavender’s investigative exploits, I was shocked to discover that he had died at the relatively young age of 44, in 1833. Unfortunately, although I was able to locate his burial record, I couldn’t find out how he had died, as the issuing of death certificates didn’t begin for another four years. However, his obituary in the press provided some intriguing additional information about his life and work. Firstly, the newspaper revealed that he had a wife and nine children. I investigated this further, and discovered that he had married Sarah Carpmeal in 1810, shortly after being appointed to the Bow Street Runners. They had five daughters and four sons, the youngest of whom was only five years old when their father passed away.

Stephen’s obituary also disclosed that he had been involved in the investigation into the Cato conspiracy in 1820, in which he and his fellow officers uncovered a plot to murder the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, and members of his cabinet. Activist Arthur Thistlewood killed a police officer during the raid and fled the scene. According to the Lancaster Gazette, Lavender traced the perpetrator to ‘an obscure lodging’, where he apprehended him in his bed.

In an article about the Manchester police, published in the Manchester Times in 1839, Lavender was described as having been ‘an excellent officer in all respects’. He was recognised for having improved detection in the city, due to his experience as an investigator in London.

Stephen Lavender’s work gives valuable insight into early pre-Victorian nineteenth century policing practice, especially in that he was engaged by private individuals (there was no public prosecution at the time) and that he was deployed all over the country and not restricted to the vicinity of Bow Street, where he was based. I also enjoyed learning about the type of offences which were typical during that period, such as highway robbery and particularly the hunt for escaped French prisoners!

Stephen Lavender is an excellent example of an effective and efficient early police detective within the context of the Bow Street Runners. The history of this force, which spanned almost a century, however, is complex and can often seem confusing, as it operated many different patrols and there were some significant changes through the decades. I’ve delved deeper into its history and in The Confidential Files (for paid subs) this week, I’ll be examining this prototype investigative force in more detail, with a timeline of key developments, as well as an exposé of some of the myths!

Next time in The Detective’s Notebook, I’ll be exploring the puzzling historical homicide case of Edwin Bartlett, who died from chloroform poisoning, and whose wife Adelaide famously stood trial for his murder.