After my first onboard crime history lecture series for Seabourn Cruises, I disembarked in Edinburgh, where I spent a few days exploring the city. Close to my accommodation was the famous Deacon Brodie’s Tavern, which commemorates the intriguing dual existence of William Brodie, a respected craftsman and council member by day, and a profligate housebreaker by night. There are many legends relating to his fascinating story, such as his being hanged on a gallows that he had designed, and that his case inspired Robert Louis Stevenson to write Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. I decided to investigate…

A promising start

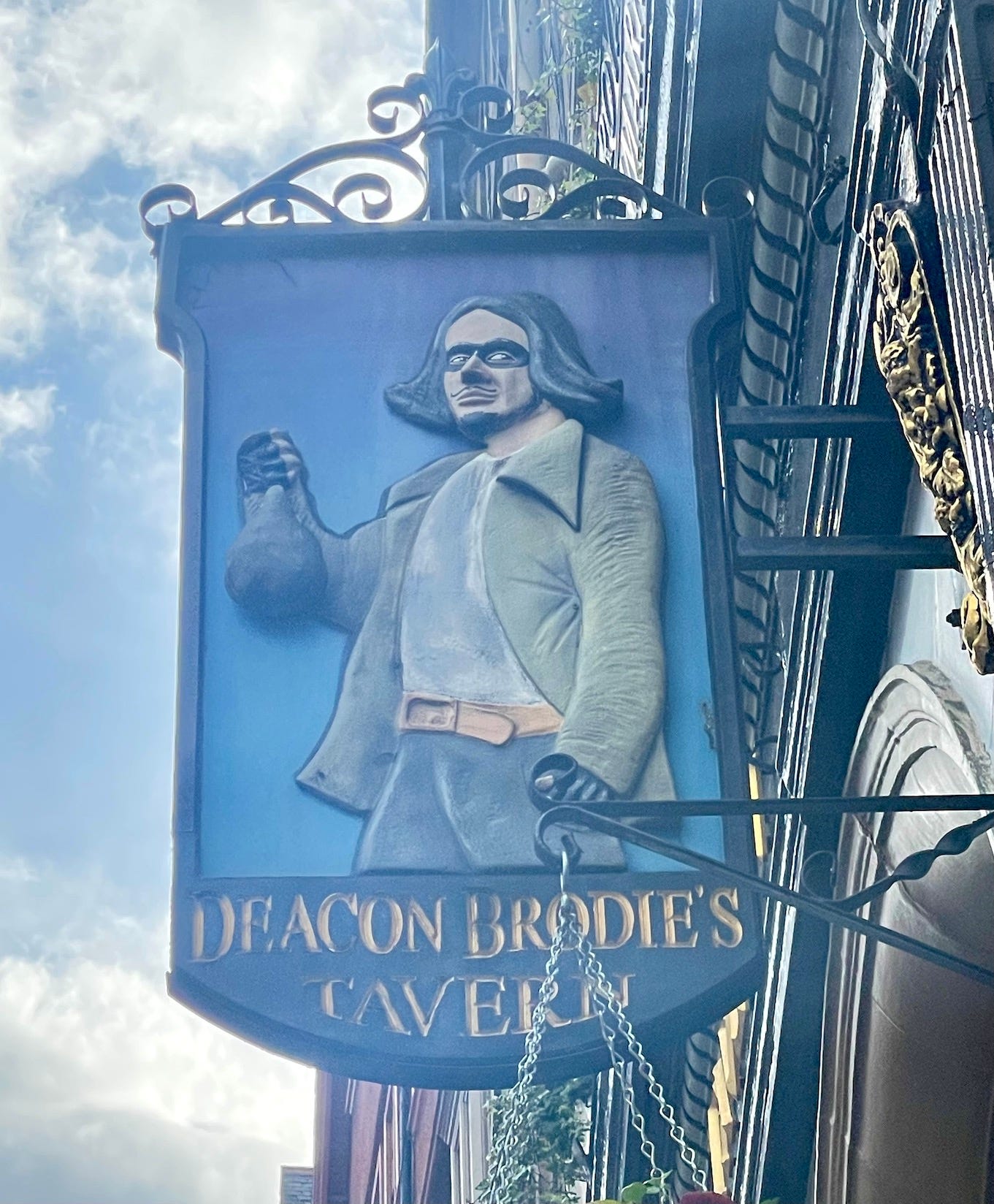

The tavern, which is on Lawnmarket on the Royal Mile, has a double-sided sign. One shows Brodie dressed in fine clothes and holding a set of golden keys – he was a locksmith and had access to many grand houses throughout the city. The other side depicts him as a grey-faced felon, with plain clothes and stripped of his status as he faced the gallows. A plaque tells his story.

William Brodie was born in Edinburgh on 28 September 1741, the son of a cabinetmaker. A deacon of Wrights and Masons Guild, he was elected deacon councillor of the city in 1781. However, under cover of darkness, he ‘was a gambler, a thief, dissipated and licentious’. Brodie was convicted of robbery and hanged near St Giles on 1 October 1788, a few yards from the public house which now bears his name. On the other side of Lawnmarket is a café, Deacon’s House, the ground floor of which was Brodie’s workshop.

I began my investigation by trying to uncover William’s background and history. I found that his parents were Francis Brodie, who was a wright and cabinetmaker, and Cecilia Grant. William married Ann Petrie on 13 November 1782. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, William took over his father’s business on his death. The Williamson’s Directory for the City of Edinburgh, Canongate, Leith and Suburbs confirmed that he was living at Brodie’s Court in 1782 and working as a wright. This is the same site as the café.

Turning fortunes

Despite his considerable civic achievement, at an early age, William developed a gambling habit and he was known to frequent a disreputable betting house in Fleshmarket. In 1786, he met three men; George Smith, Andrew Ainslie and John Brown, with whom he formed a gang to commit burglaries throughout the city. An account of the Trial of William Brodie and George Smith written by bookseller William Creech, who was a juror at the trial, describes the men’s downfall.

On 5 March 1788, Brodie and his gang broke into the excise office in Chessel’s Court, Canongate using false keys, and stole money amounting to £16, which is about £2,000 in today’s value. When his partner in crime John Brown, also known as Humphrey Moore, was arrested, as he had a previous convictions for sheep stealing in England, he turned king’s evidence to avoid transportation for his earlier offence and maybe an even worse fate for the present one. He informed the authorities that Brodie had planned and led the robbery. However, by this time, William fled the city and left Scotland for Amsterdam, where he was arrested the night before he planned to travel on to America.

William Brodie and George Smith were tried at the High Court of Justiciary, Scotland’s supreme criminal court, on 27 August 1788. Their former associate John Brown identified them at the bar. As noted in the trial account:

A more notorious and hardened villain than Brown had not, perhaps, been ever produced on such an occasion.

Andrew Ainslie, a shoemaker, testified against his former associates. He told the court how he and Brown had staked out the excise office over several nights before the break-in. They learnt that the doors were locked at 8 pm and that a night watchman arrived at 10 pm to guard the premises during the night. The pair also procured a plough coulter (a mounted knife) and two iron wedges for the burglary. On the night of the crime, the men had gathered at Smith’s house. William Brodie arrived later than the others; he was wearing a light-coloured great coat over dark clothing and a cocked hat. Brandishing a pistol, he was singing a highwayman’s chanty. Ainslie went ahead of the others to watch the premises and then informed them when everyone had left. Smith opened the door to the office with the keys. Brodie and Smith arrived and went in, carrying six loaded pistols between them. Ainslie remained outside to stand guard. After a short while, the shoemaker spotted two men coming out of the office, neither of whom he recognised. After giving the prearranged signals of three whistles, he fled the scene.

John Brown took the stand next and stated that the four of them had planned the burglary four months earlier, in November 1787. He then described what had taken place inside the office on the night in question. When he entered the excise office, he saw Smith had opened the door of the cashier’s room with some curling irons. They used the coulter and a crow bar to force open the inner room. Once inside, they ransacked the desks and drawers for cash, which resulted in their finding £16. Hearing movement from upstairs, they cocked their pistols. Not hearing Ainslie’s warning, they decided that, as there might be clerks in the building, it was time to leave. As they ran back into the main office, they discovered that Brodie had already left. Brown confirmed that Smith had made the key and Brodie had produced a lock pick, both of which were produced as evidence in court.

After the testimonies of 27 witnesses for the prosecution, and seven for the defence, the trial closed for the day while the jury considered their verdict. On the following morning, they took their places back in court and announced that they had found both defendants guilty. During the judge’s final address, he lamented that William Brodie, despite his education and position in life, had given into ‘gentlemanly vices’ which had been ’the source of his ruin’. He sentenced them both to death and they were hanged on 1 October. I haven’t been about to find any evidence that the gallows were designed by Brodie.

Literary inspiration

After discovering the truth of the criminal act and subsequent trial of William Brodie I then wanted to know whether his story had inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous novel. I went to the writers’ museum, just off the Royal Mile, to find out more. In a display case at the museum is a copy of a play written by Stevenson with William E Henley over a century after Brodie’s execution. It is called Deacon Brodie, or the Double Life and was performed at the Prince’s Theatre, London on 2 July 1884, just two years before the publication of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Also, at the writers’ museum is a mahogany cabinet from the Stevenson home, which was in Robert’s bedroom during his childhood. It was made by none other than William Brodie.

So it is conceivable that this notorious eighteenth century case was the basis for the legendary Victorian Gothic story.