Murder at the Met

150 years of Scotland Yard’s Crime Museum

Scotland Yard’s infamous ‘Black Museum’ was created in 1875 and, during the last 150 years, it has collected and curated artefacts from many crimes, including some iconic historical homicides. To mark this important anniversary, the Metropolitan Police Museum has created an exhibition of some of the most memorable objects from the crime museum, which offers a unique glimpse of some of the collection, which is closed to the public.

I had a tour of the exhibition with the Met Museum’s curator, Dr Claire Smith, who gave the fascinating, and often gruesome, histories of these unusual and rather chilling exhibits. I’d like to share five of the murder cases included in the display.

1. Frederick Bailey Deeming, 1892

One of the most famous set of items held by the Crime Museum is its collection of death masks of murderers, which were made from casts of their heads after their execution. The exhibition features that of serial killer Frederick Bailey Deeming, who was convicted of the murders of his children and two wives.

Originally from the village of Rainhill, Merseyside, Frederick married Marie James in 1881. The following year, the couple emigrated to Sydney, Australia, where Frederick found work with an importer of plumbing and gas fitting supplies. Over the next few years, the Deemings had three daughters and a son. The family eventually returned to England, with Frederick leaving again for extended periods overseas. In the late 1890s, he began a relationship with another woman, Emily Lydia Mather, whom he married under a false name. They travelled to Australia together. In 1892, Emily’s body was found under the floor of a house in Melbourne. Back home, it was also discovered that Frederick had killed Marie and the four young children. He was convicted of murder and executed.

Frederick Deeming was also suspected by some to have been ‘Jack the Ripper’ and, although this was dismissed by the Metropolitan Police in 1892, the belief still persists today.

2. The Stratton brothers, 1905

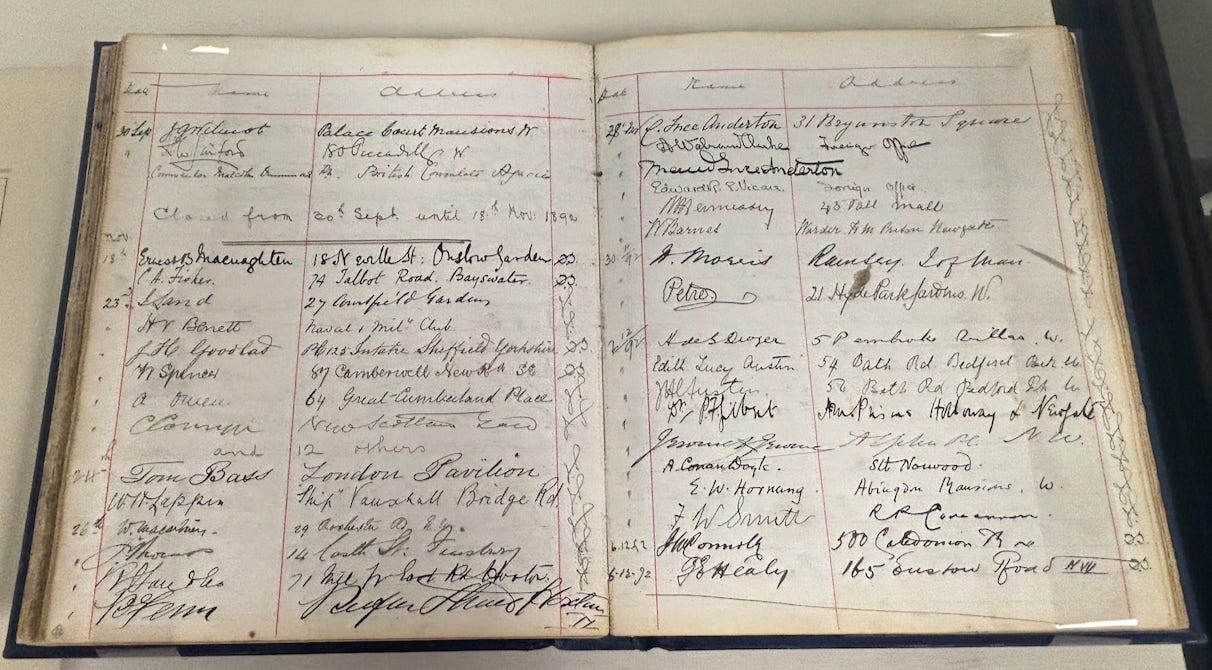

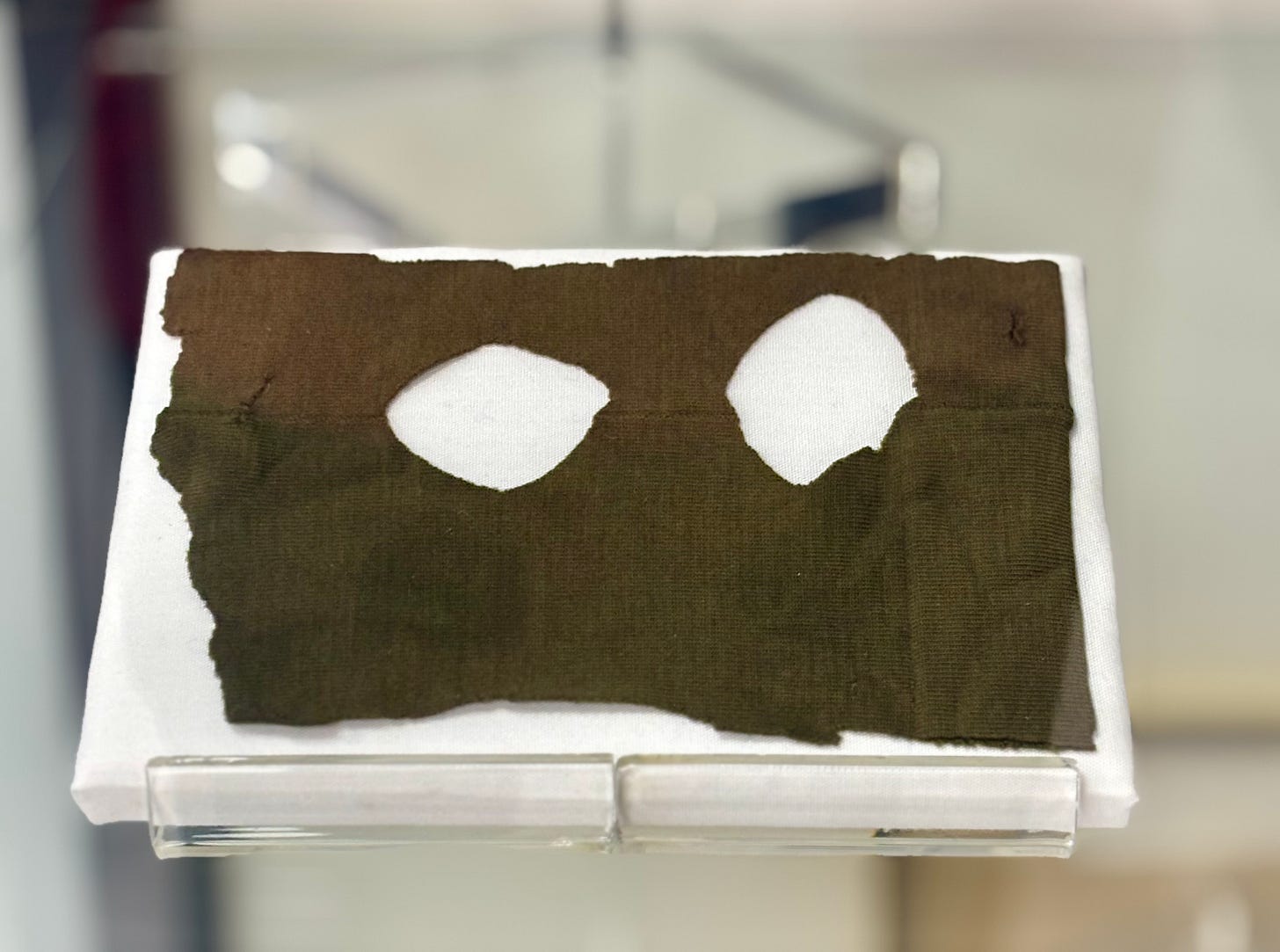

Some historical murders are remembered because of their place in crime history and the Stratton brothers’ case is significant as it was the first time that fingerprinting was used to solve a homicide in Britain. The mask used by one of the perpetrators is included in the exhibition.

On 27 March 1905, the body of Thomas Farrow was discovered at his chandler’s store on Deptford High Street. His wife, Ann, had also been attacked. She was taken to hospital where she died three days later. When the police examined the crime scene, they found an empty cash box and two masks made from silk stockings. On further analysis, they managed to lift a bloody thumbprint from the metal box. Their ongoing inquires revealed that two local men, Alfred and Arthur Stratton, had suddenly disappeared and, as they both had previous convictions for housebreaking and burglary, suspicions were aroused. Within a week they were arrested and, when their prints were compared to the one from the cash box, it was a match for Alfred. This incriminating evidence led to their conviction and execution for the double murder.

Just to mention that the first ever murder case to be solved by fingerprinting was in Argentina in 1892, and you can read about it here.

3. Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen, 1910

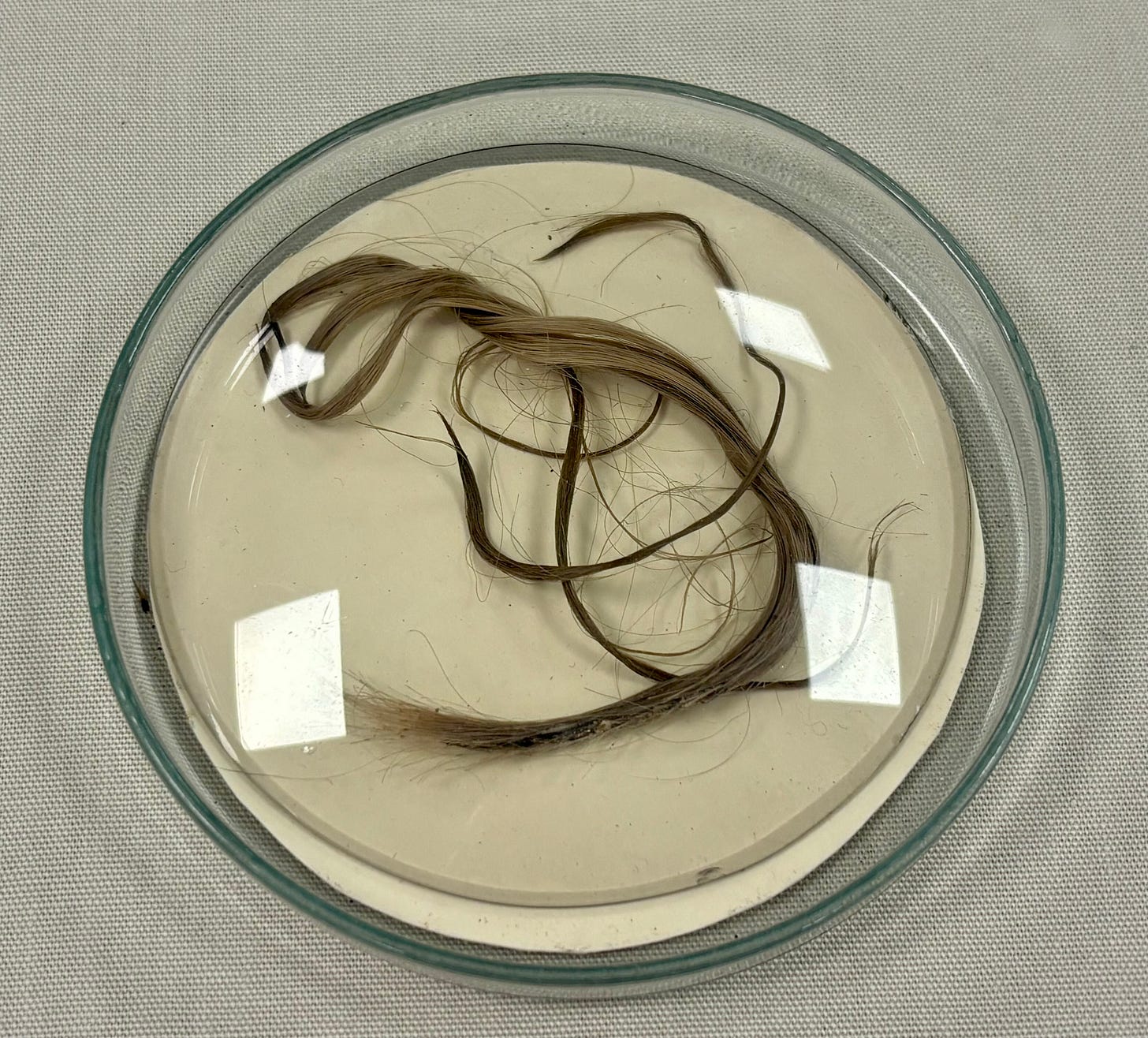

In the exhibition there are several artefacts from the well-known murder of Belle Elmore by her husband Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen in north London. Belle, who was a music hall artiste, disappeared in January 1910, and Hawley told everyone that she had returned to their home country of America to attend a sick relative, where she herself had succumbed to illness and died. Scotland Yard detective, Walter Dew, later found her remains under the cellar floor at their home in Islington, which led to a transatlantic chase to bring Dr Crippen to justice.

On display at the Metropolitan Police Museum is a copy of a contemporary account of the murder case, a letter from the assistant commissioner of the Met to the solicitor requesting permission to examine Belle’s effects, and a sample of her hair (above), which was key evidence in the case. Also, there is a potential suicide note written by Crippen to his lover, Ethel le Neve, who fled with him:

I cannot stand the horrors I go through every night any longer and as I can see nothing bright ahead and money has come to an end I have made up my mind to jump overboard tonight. I know I have spoil [sic] your life but I hope someday you can learn to forgive me. With last words of love, your H.

Finally, there is a dissecting knife used by Sir Bernard Spilsbury, who confirmed that Belle had died from hyoscine poisoning. I found this object quite disturbing!

4. The Brides in the Bath murders, 1912

One of the most shocking and complex series of homicides included in the exhibition is known as ‘the Brides in the Bath’ murders. This began with the death of Margaret Elizabeth (née Lofty) Lloyd in her bath in London in December 1914, which was considered to be accidental drowning. When the incident was reported in the press, it reminded Charles Burnham of the demise of his daughter, Alice, who had died in similar circumstances in Blackpool the previous year. She had been married to George Joseph Smith. The matter was reported to the police who opened an investigation and, when they discovered that George Smith was the real identity of Margaret Lloyd’s husband, which led to a nationwide inquiry in more than 40 towns and involved interviewing some 150 potential witnesses. A sinister pattern emerged, and the police located another possible victim, Bessie Mundy, who had also perished in her bath.

George Joseph Smith had a complicated history of relationships. His modus operandi was to court and marry bigamously (he had only one legitimate wife who remained unharmed) and, after encouraging his ‘wives’ to hand over their savings or take out life insurance, he would drown them. However, due to the nature of his crimes, it was difficult to prove that the women have been murdered. All that changed when pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury took charge of the forensic examination.

The biggest challenged Spilsbury faced was that the bodies were by now in an advanced state of decomposition. In a rather brilliant move, he had all three baths, one of which is in the exhibition together with a photo of Smith with Bessie Mundy, brought to London and, at Smith’s trial, he successfully demonstrated how the women were drowned and disproved his contention that they had experienced fainting fits. George Smith was convicted and given the death penalty.

5. The Crumbles Murder, 1924

In April 1924, Emily Beilby Kaye travelled to Eastbourne to spend a few days with her lover, Patrick Mahon. The shorthand typist and the sales rep (who was married) had met two years earlier through work, and they were planning a new life together. Or so Emily thought. Ten days later, when Patrick’s wife became suspicious of his absence, she contacted Scotland Yard. The investigation led to the discovery of Emily’s dismembered body in a travelling trunk at the property where she had been staying with Patrick. He was tried for her murder and sentenced to death.

One of the most interesting aspects of this horrific crime is the examination of the crime scene by the leading pathologist of the day, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, which helped secure Patrick Mahon’s conviction and resulted in the creation of a ‘murder bag’ for use by detective officers (I’ll share the full details of this case in a future post). The Met Museum exhibition features two artefacts from this case – a savings book belonging to Mahon and, more importantly, the model furniture from the house in Eastbourne, which was used to recreate the crime scene. For the purposes of the exhibition, a copy of the items were made using a 3-D printer, and these are displayed alongside the originals.

I have had the privilege of visiting the Crime Museum at Scotland Yard and I reported on my experience in The Confidential Files (for paid subs), which you can read here. If you’d like to visit the exhibition at the Metropolitan Police Museum, you can find out the details here.

Later this week, also in The Confidential Files, is an examination into the history of the practice of identity parades, which was used as a detective strategy in many cases in the past, including the investigation into the Whitechapel murders in 1888.

And finally, next time in The Detective’s Notebook, I’ll be investigating a rather tragic murder which I uncovered in my doctoral research.

When I first read the headline, I thought the article would be about the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. Reading the article I realized I was wrong. As I like the old time radio show The Black Museum., I really enjoyed this article.