Prior to the change to my ‘new’ newsletter, The Detective’s Notebook, I was looking back over my previous posts and I realised (to my horror!) that I hadn’t written properly about my all-time favourite detective, Jerome Caminada. I’m now going to rectify that oversight by introducing this trailblazing investigator, who was a true Victorian super sleuth and a real-life Sherlock Holmes.

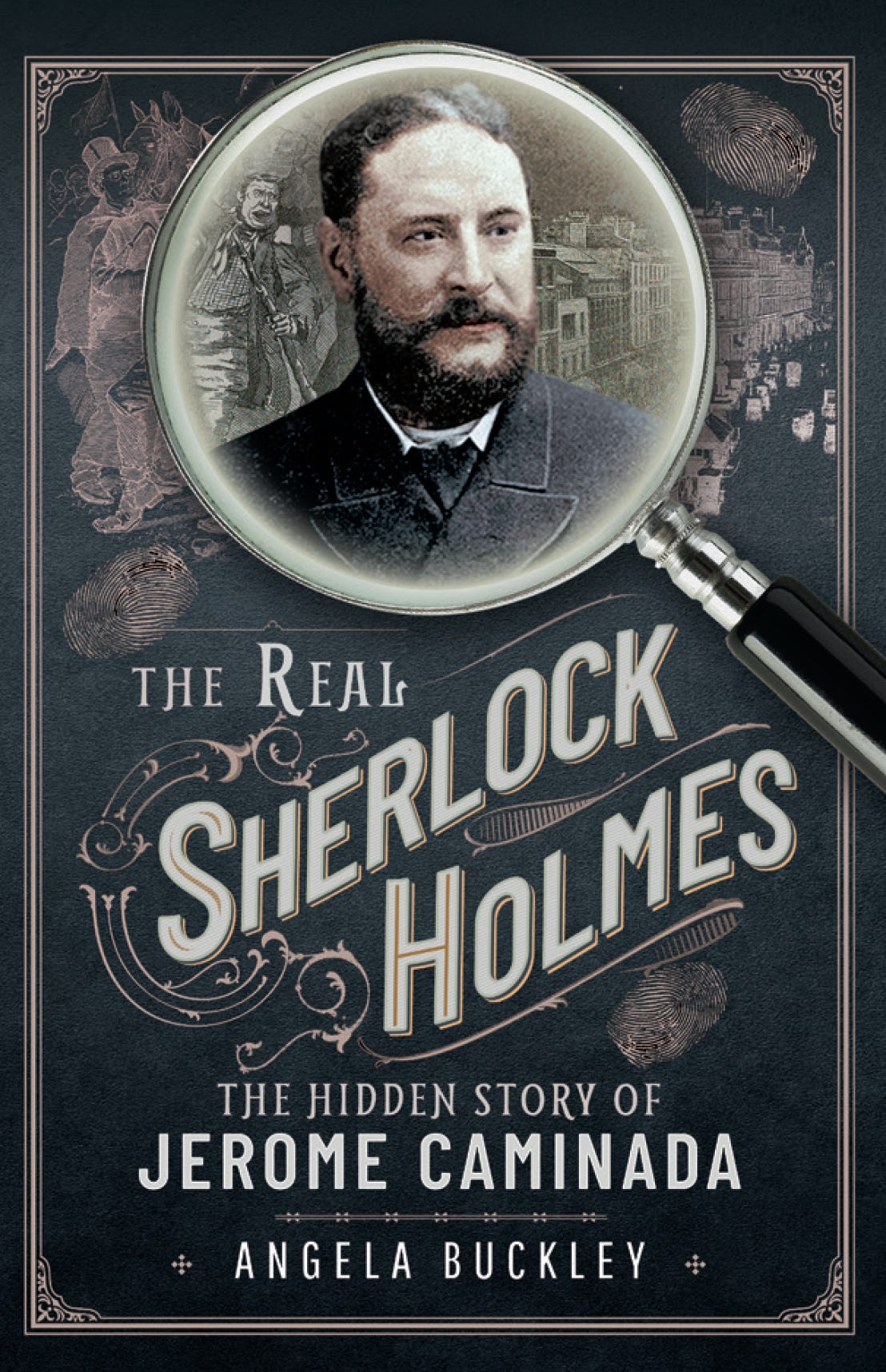

Based on the two volumes of his memoirs, I wrote a biography of the legendary detective. When it was published, it attracted a lot of unexpected attention. I was interviewed by the Sunday Times, after which articles appeared all over the national and international press. A highlight was when a relative called from Australia to say that she had read about my book in the Sydney Morning Herald. Articles about Caminada were published also in Canada, India, Ireland and Italy. As the popular series of Sherlock starring Benedict Cumberbatch was airing at the time, there were lots of lighthearted comparisons between the fictional detective and his so-called real-life counterpart. I wrote articles about him for the Sunday Express, All About History magazine, and other publications. I also had the opportunity to make a short film for The One Show, which was great fun!

So, enough with the reminiscing and here’s an intro to one of the greatest, and less well known, Victorian detectives…

On the evening of 6 December 1886, Arthur Foster left the Queen’s Theatre, Manchester, with a pocket full of gold and a bejewelled lady on his arm. He hailed a hansom cab and as the couple settled into the carriage, a shadowy figure slipped in beside them. Unaware he had been tailed throughout the day, Foster was horrified to see the unmistakeable, bearded face of Detective Chief Inspector Jerome Caminada. Known as ‘the Birmingham Forger’, Arthur Foster was wanted by the police for a serious fraud and, once again, Detective Caminada had caught his man.

In 1886, the year before the début appearance of Sherlock Holmes in A Study in Scarlet, Detective Caminada was at the top of his game. He had been policing the crime-infested streets of Manchester for more than two decades, and had proved himself to be one of the city’s finest detectives and the nemesis of the nefarious criminals that plagued its dark underworld. In the years following the arrest of the Birmingham Forger, he became renowned throughout the country, as he tackled a ruthless career criminal, tracked Fenians abroad and at home, and captured an escaped political prisoner. In 1889, at the height of his dazzling career, he would face his most baffling case yet: ‘The Manchester Cab Mystery’. However, although he was often compared to his fictional counterpart, Caminada’s own story could not have been more different.

Humble beginnings

Jerome Caminada was born to immigrant parents on 15 March 1844 in Deansgate, Manchester, opposite the site of the infamous Peterloo Massacre. The decennial censuses chart a precarious childhood in some of the worst quarters of the city. The family of Jerome’s father, Francis, who was a cabinetmaker, had originated from Lombardy, Italy. When they arrived in Manchester in the early 1800s, the cotton industry was burgeoning beyond expectation and the city was undergoing unprecedented change, as thousands of manual workers poured in to find employment in the factories and mills. Like many others around them, the Caminadas suffered grinding poverty and the ever-constant threat of disease.

When Jerome was just three years old, his father died and, by the time he was fourteen, he had also lost four young brothers and a sister, in the direst of circumstances. Soon after, he was forced to move into the heart of the city’s slums with his mother and surviving siblings. In the sordid streets of this notorious rookery, Caminada gained an intimate knowledge of the thieves and crooks who lived in the closed courts and labyrinthine alleyways, and this ‘apprenticeship’ served him well when he joined the Manchester City police force in 1868.

Police Constable Caminada was attached to A Division, his own neighbourhood, and during his first week, he was ridiculed, insulted and even assaulted, and soon realised that ‘a policeman’s life was not a bed of roses’. However, the young officer showed such aptitude for detective work that after just three years of service, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and transferred to the detective department. His career in fighting crime had begun in earnest.

Detective Jerome

Known as ‘Detective Jerome’ by the criminal fraternity, because they struggled to pronounce his foreign surname, Caminada tackled all manner of shady characters and insidious wrongdoers during his early career. Beginning with racecourse duties, he soon became adept at spotting pickpockets and con artists. Often employing a disguise, he would shadow suspects through the crowds, before pouncing on them at an opportune moment to secure their arrest. His high-profile investigations included quack doctors, fake heir hunters and the participants of a cross-dressing ball. During the course of his work, he infiltrated illegal beer houses, gambling dens and houses of ill repute, as he exposed crime and apprehended the perpetrators. Details of his exploits were regularly reported in the local press and the detective constantly made the headlines.

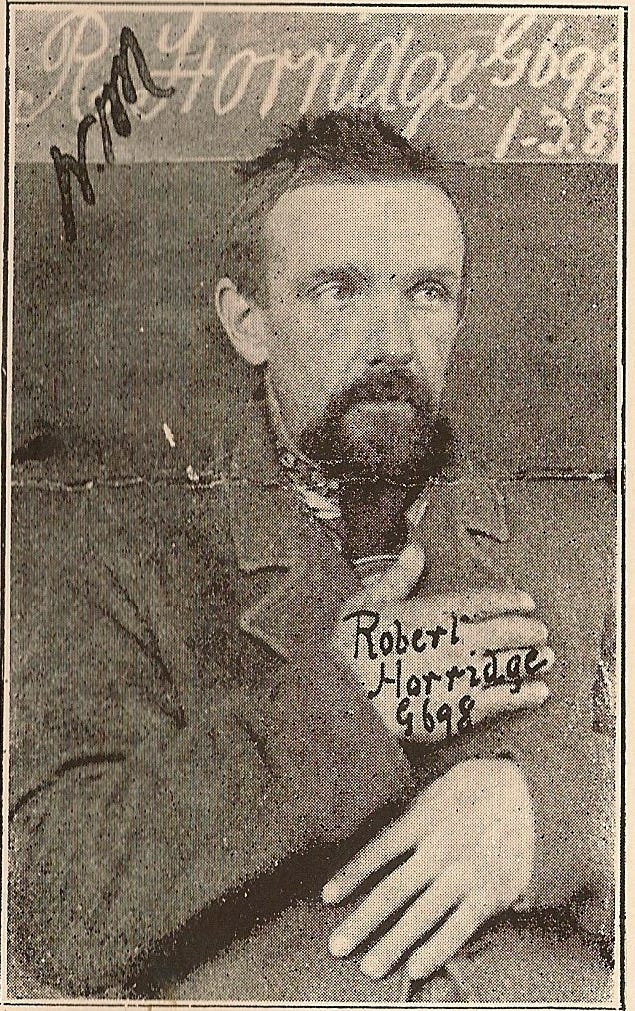

Detective Caminada even had his own ‘Professor Moriarty’: Bob Horridge was a violent burglar, who would stop at nothing to preserve his freedom. When Caminada arrested the thief for the first time as a police constable, Horridge vowed that he would kill him. Their rivalry would last for 20 years. In 1887, after Horridge shot two policemen during a robbery, the detective vowed to end his reign of terror once and for all, which led to a dangerous confrontation between the two adversaries. With Horridge finally behind bars for good, Detective Caminada’s career rose to unprecedented heights.

On 26 February 1889, paper manufacturer John Fletcher hailed a cab from the steps of Manchester Cathedral, in the company of a young man. Later that evening, the businessman was found dead in the hansom and his companion had disappeared. This mysterious death was placed in the capable hands of Detective Caminada and within the record time of just three weeks, he deduced that Fletcher had been poisoned, tracked down the culprit and brought him to justice. This astonishing case bore all the hallmarks of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and catapulted Jerome Caminada into national fame as the Victorian public avidly followed the twists and turns of the story in the newspapers. However, despite the success in his professional life, Caminada faced considerable challenges at home.

In 1881, at the age of 37, Jerome Caminada had married Amelia Wainhouse, the daughter of an Irish ribbon weaver. Despite also coming from humble roots, the Wainhouse family had fared better than the Caminadas and Amelia had enjoyed a more stable childhood. Jerome and Amelia set up their first home in Old Trafford, a leafy suburb, not far from the city centre (and near to my childhood home). They had five children, but sadly the first three died in infancy. Despite these personal tragedies, Detective Caminada continued to work tirelessly to clean up the streets and make Manchester a safer place. By the late 1880s, he had been promoted to the position of detective chief inspector and there were even more exciting adventures to come.

Undercover missions

After his rise to local and even national fame, Detective Caminada undertook a number of important assignments and faced some of the most threatening situations in his daily work, including the deadly gangs of ‘scuttlers’ (street fighters), bands of anarchists and Irish nationalists. At the height of the Fenian dynamite campaign, Caminada tracked suspects throughout Britain and to other countries, such as France, Ireland and America. Back home, he tackled seductive swindlers, sophisticated confidence tricksters and even child murderers.

Towards the end of his career, Jerome Caminada wrote his memoirs, in which he revealed that for almost three decades he had been involved in covert missions for the British government. Detective Superintendent Jerome Caminada retired in 1899, after 31 years’ service. The Evening Telegraph described him as ‘one of the most noted detectives of the country, a man of whom Manchester has been pardonably proud.’ Dubbing him ‘a terror to evil doers’, the article celebrated his achievements:

His career has been one of the most remarkable and brilliant in police annals. Probably no man living knows more about crime and criminals, their habits and habitats, their cunning and duplicity.

After retirement, Jerome’s active life continued unabated as he set up his own private inquiry agency and served as a city councillor. In 1911 he was injured in a coach accident, whilst on holiday in North Wales, from which he never fully recovered and on 10 March 1914, five days before his 70th birthday, he died peacefully at his home in Moss Side. At his funeral service, his long-standing colleague Judge Parry praised his sterling qualities and unorthodox methods: ‘He was a man of resource, energy, and initiative, and he never stultified himself by a petty adherence to office regulations. He was the Garibaldi of detectives’. He also described Caminada’s kindness, sense of justice and loyalty; all qualities that had stemmed from the challenging experiences of the detective’s early life in the slums.

You can find out more about Detective Caminada’s sleuthing adventures in The Real Sherlock Holmes.

Since the publication of his biography, I’ve studied many more Victorian and Edwardian police detectives and I haven’t yet come across a story quite as compelling as Jerome Caminada’s. A decade later and now that I’ve completed my doctoral research on detective history, I’m ready to embark on some new projects involving him – I shall keep you updated!

Later this week in The Confidential Files, I’ll be sharing three cases from Jerome Caminada’s fascinating casebook, as well as offering subscribers a free copy of Detective Caminada’s Casebook, an edited version of the first volume of his memoirs.

Next time in The Detective’s Notebook, I’ll be examining the mysterious murder of Charles Bravo, an iconic real-life poisoning case which has baffled true crime enthusiasts for almost 150 years.

Reding more about the taxi case would be fascinating. I imagine you cover this in the book?