In December 1913, the inhabitants of Liverpool were shocked by the brutal murder of Christina Bradfeld, whose body was discovered in the canal. There were two obvious culprits, both of whom worked for her family’s business, but it was not clear which one had dealt the fatal blows. The police turned to the medical experts, who managed to work out, using blood analysis, which suspect was the killer.

I studied this tragic case for my doctoral research and it reveals how in the early decades of the twentieth century, police detectives had begun to apply forensic science to homicide investigations.

A deadly crime

On the evening of 10 December 1913, Christina Bradfield, aged 40, was locking up the shop of her brother’s tent and tarpaulin manufacturing works at the end of a busy day of business. John and the typist had left the premises at 6 pm and, as was customary, Christina put the day’s takings in her satchel and picked up the keys to close the shop. No one saw her leave but, an hour and a half later, a ship’s steward was passing the store on the way to meet his girlfriend, when a shutter fell from the building and damaged his bowler hat. The clatter brought two men out of the shop to see what was going on. They offered him some compensation and then went back inside. A short while later, they came back outside again, this time with a handcart which they pushed in the direction of the canal.

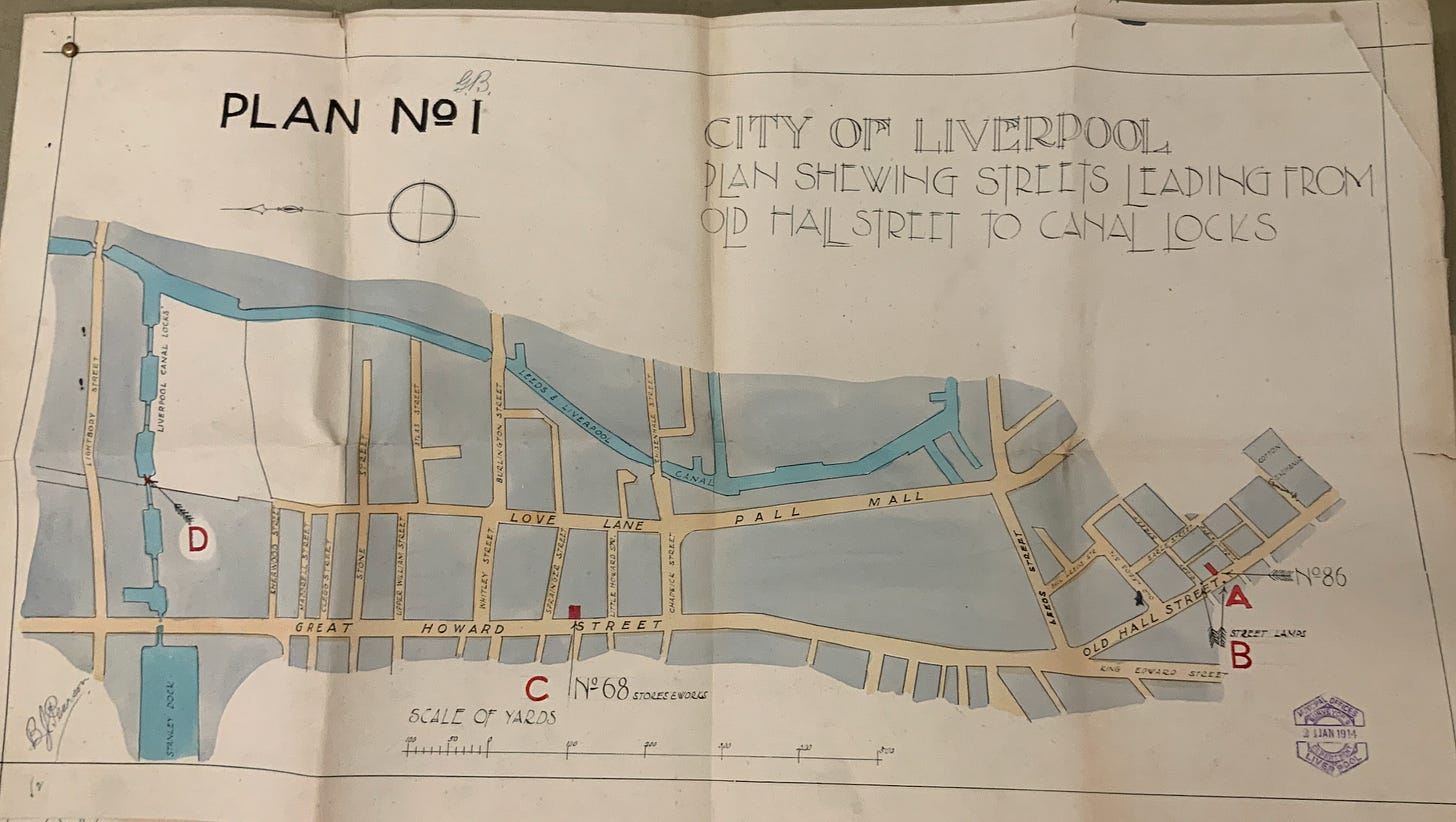

At 12.30 pm, the following day, the owner of a narrowboat on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was trying to open the railway lock gates, when his boat hook caught on a sack submerged in the water. To his horror, he saw that there were two feet protruding from the parcel, which was tied round the waist and ankles. The body was later identified as Christina Bradfield, who had been bludgeoned to death with a heavy instrument. Some of the lacerations to her head, which were too numerous to count, had gone right down to the bone. She also had defensive wounds to her hands, which suggested that she had faced her attacker and probably knew them.

The hunt for the suspects

Christina Catherine Bradfield lived and worked with her widowed brother John, who owned the business. They came from a large family with nine children. When Christina was three, her father died and her mother had to work as a draper’s clerk to keep the family afloat. In 1890, at the age of 17, she lost two brothers within a few weeks of each other. She was described in the Liverpool Daily Post as a ‘quiet, inoffensive, and good living woman, always attentive to her business, and always kind to her brother’s employees.’

The suspicion for this terrible act fell on the two employees who were seen at the shop that night. George Ball (also known as George ‘Sumner’) was 22, had worked for the Bradfields as a packer for six years. His colleague Samuel Angeles Eltoft, aged 18, had recently joined the business as an errand boy. Both men were responsible for sewing up the sacks in the evening which contained the rubbish ready for the dustcart.

After circulating posters with the descriptions of the suspects (after which the case became known as 'The Liverpool Sack Murder’ in the press), Detective Superintendent Duckworth, of the Liverpool City Police, visited Samuel’s lodgings, where he discovered bloodstained clothing and a box of obscene photographs in his bedroom. As Samuel was present at the house, he arrested him there and then. His alleged accomplice, however, had disappeared.

Several days later, on 20 December, a member of the public recognised George Ball in the street and informed the police. George had remained nearby but he had tried to disguise himself by shaving his eyebrows to a thin line and wearing an eye patch. He had also donned a pair of dungarees usually worn by sailors. When the police apprehended him, they found the victim’s watch in his possession. The two men proclaimed their innocence, with George saying that a third man had committed the murder and then forced them at gunpoint to dispose of the body. He explained: ‘We put the sack in the canal, thinking we were clear’ (Liverpool Daily Post, 14 January 1914). Despite their claims, both were charged with Christina’s murder. However, there was no obvious evidence to as to whether they were both guilty or whether one of them had killed Christina and the other had helped to get rid of her body.

Science solves the case

After measuring the marks made on the ground by the canal where the body was dragged, the detectives removed some bloodstained wood from the scene. They also took some bloodied clothing from the shop. Then they sent all the evidence, as well as the suspects’ clothes, a tarpaulin, and the sack in which the body was wrapped to Professor David Moore Alexander at the University of Liverpool for chemical analysis.

Professor Alexander submitted 17 samples for testing. After a chemical test, he used a spectroscope, which identifies the chemical composition of a substance by examining the light absorbed by it, and a microscope to ascertain if any of the items showed evidence of blood – ten samples tested positive. He then submitted them to further tests, using a precipitate of rabbit serum, to see if the blood was human. The professor concluded that the evidence taken from the scenes, such as the wood, the sack and the tarpaulin, did in fact show traces of human blood. And, most importantly, George’s clothing was covered in blood, but Samuel’s was not, thus making it more likely that the older man had been responsible for Christina’s murder.

George Ball and Samuel Eltoft were committed to trial at the Liverpool Assizes on 2 February 1914. George stuck to his story about the unknown third man, adding that Samuel hadn’t entered the shop until after the murder, and then they had both taken Christina’s body to the canal. Despite a seeming lack of motive for such a violent act, except for perhaps the money Christina had been carrying which amounted to £5, George was convicted of her murder, and Samuel as an accessory after the fact, for which he was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. George received the death penalty and was executed on 26 February 1914 at Walton prison. Before he went to the gallows, he confessed to having killed Christina.

This is a remarkable story and a clever use of early forensic science. There are other aspects to consider — could the blood have belonged to someone else? Perhaps, the novelty of these methods also meant that defence attorneys were not ready to challenge such findings.

Thank you for sharing!