Detective history in 10 objects

The everyday tools of Victorian and Edwardian investigators

After two real-life murder cases on the recent pages of The Detective’s Notebook and before another even more gruesome (and famous) one, I thought I’d pause with a ‘lighter’ examination of the history of Victorian and Edwardian police detectives through the equipment they used to solve crimes, which offers a tantalising glimpse into their sleuthing work.

Just to add that I have not yet come across an instance of a Victorian police detective using a magnifying glass, wearing a deerstalker or playing the violin, but you never know…

1. The detective notebook

Detective officers had their own special notebooks, in which they kept information about individual cases. They carried them in their pocket to the scene of a crime to jot down evidence and clues, and to their interviews with witnesses to note the responses to their questions. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, when police detectives were questioned in court, barristers started to check if they had recorded their evidence at the time of the investigation or in retrospect.

This notebook is on display in the Greater Manchester Police Museum and unfortunately the pages are blank!

2. Bullseye lantern

Like their uniformed colleagues, Victorian detectives used bullseye lanterns for nocturnal investigations. Hooked onto their belt, they would use them to examine dark buildings and shady corners. If they were approaching a house where they knew suspects were lurking, they would also remove their boots so they could move silently. As well as the lantern, detective officers carried heavy, metal handcuffs which they called ‘snaps’ and, as they did not have firearms, they sometimes availed themselves of a strong stick to use as a weapon in tricky situations.

3. Disguises

In the past, detectives would don disguises and go undercover to investigate crime, especially in cases of fraud. For example, they would pose as a potential patient and visit a quack doctor. They also dressed as butchers, gamekeepers and even priests complete with clerical collar and carrying religious tracts. Also, detectives sometimes went to the effort of changing their facial appearance (as did criminals) to complete their ‘look’. Superintendent James Bent, of the Lancashire police, rubbed ‘sludge’ over his face whilst pretending to be a rough sleeper. As they travelled around the country detecting crime, they carried their extra clothing in a travelling bag, just like Sherlock Holmes.

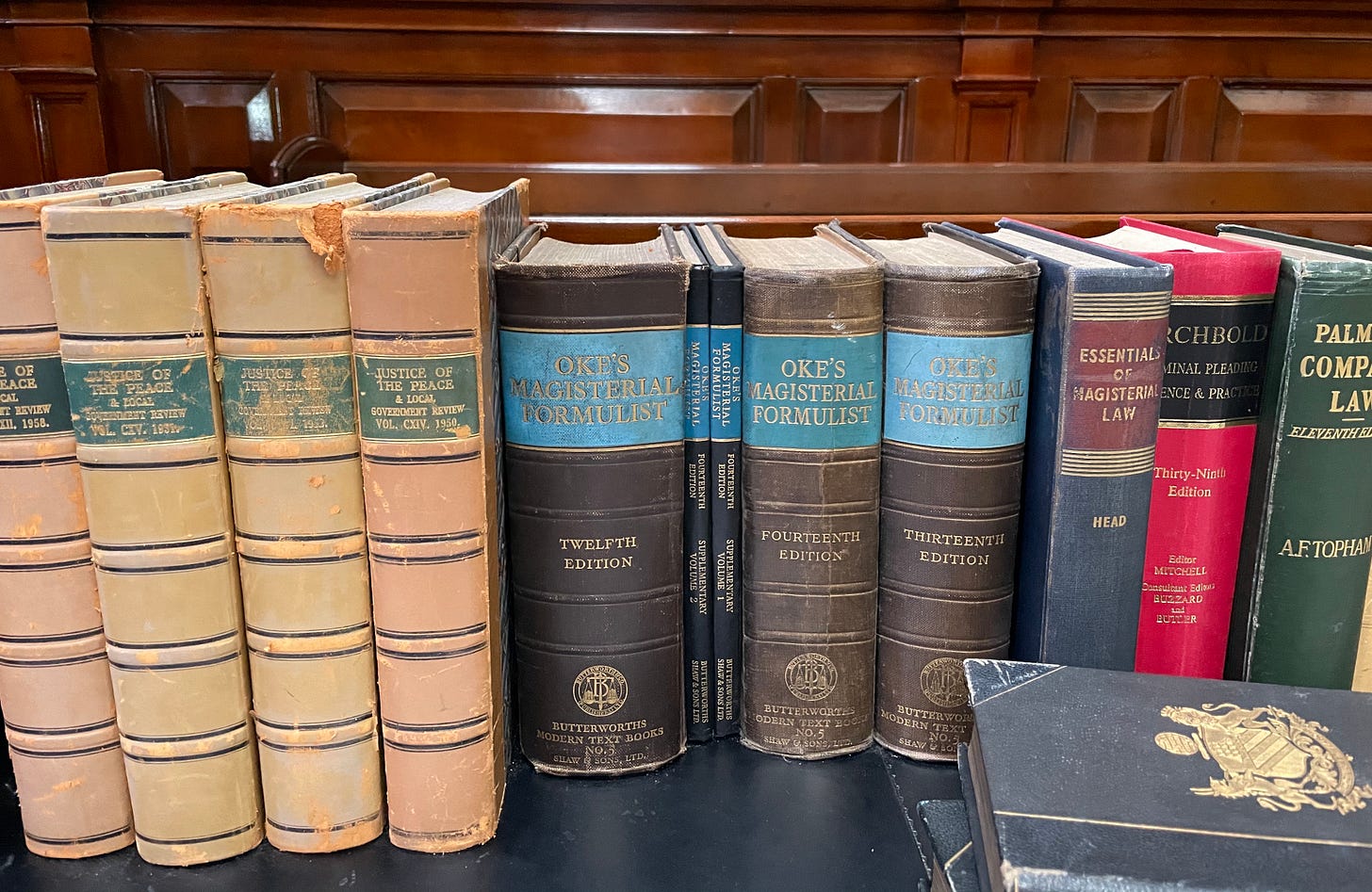

4. Law books

As detective police officers in the nineteenth century were selected and promoted internally from the uniformed ranks, they were mostly from working class backgrounds with the bare minimum of education. Some detective officers took it upon themselves to continue their education through reading law books, such as The Magisterial Synopsis: A Practical Guide for Magistrates, Their Clerks, Attornies and Constables, by George C Oke and Stone’s Justices’ Manual.

5. Crime scene cameras

As photography developed, during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the police began to take photos of crime scenes, especially when a murder had taken place. Scotland Yard reported that they required a hand or ‘snap shot’ camera for use in external locations, such as in the street or inside houses, which they had to borrow as it was too expensive for the force to buy one.

Some constabularies outsourced this practice to local professional photographers and others, like Birmingham City Police, purchased their own camera, which was operated by one of their own officers.

6. Route forms

Police officers, including detectives, relied on the ‘route form’ as the main medium of communication during the nineteenth century. This was a handwritten message, with details of crimes committed and descriptions of suspects, which was passed on foot between officers and the police stations. It was notoriously slow and inefficient but, despite this and the advent of telegrams, regional police detectives were reluctant to discard it, claiming that the route form was still an effective tool in solving crime. They continued to use it until the introduction of telephone systems in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

7. Plaster of Paris

One of the earliest CSI tools, used by police detectives, was the recording of footprints at a crime scene. This was mostly done by making a cast out of plaster of Paris, although some detectives used wax. Sometimes, they didn’t even take casts and just matched the print with a suspect’s boot in situ. Although some detective departments experimented with other substances for casting footprints, they tended to keep using the traditional method of plaster of Paris.

8. Fingerprinting kit

The Fingerprint Bureau at Scotland Yard was created by Sir Edward Henry in 1901, after which the practice was gradually introduced into regional detective departments. In Birmingham the technique was first used successfully to investigate a burglary in 1905, which was the same year that Scotland Yard solved the first murder in Britain through fingerprint retrieval and analysis.

I am the proud owner of this fingerprint kit, which is from the Liverpool City Police.

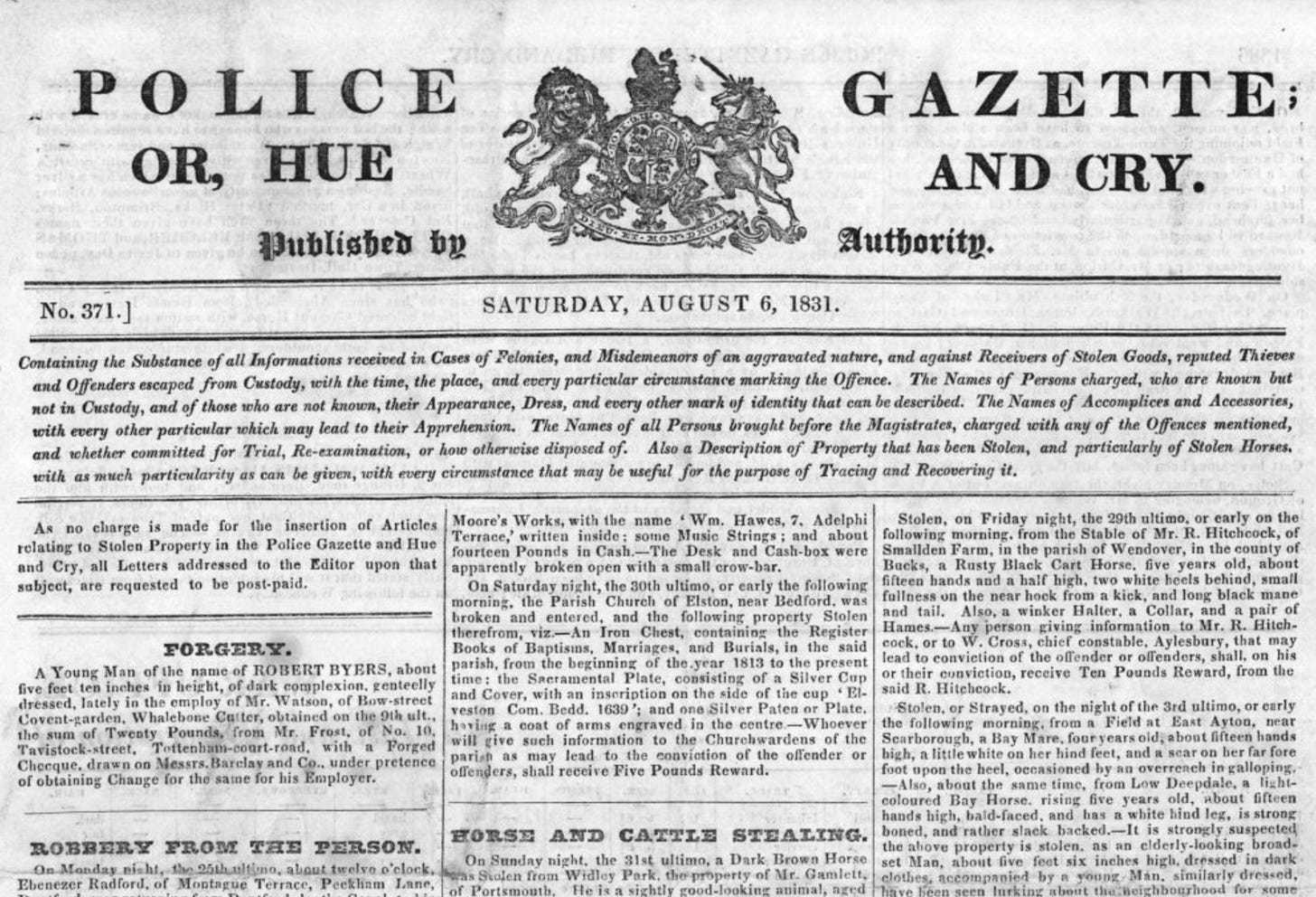

9. Police Gazette

Victorian detectives used the Police Gazette to share descriptions of suspects and stolen property. Established in 1772, it was in circulation for almost 250 years until 2017. Although some detectives used it to help them identity potential offenders, I found in my doctoral research that many copies of the publication languished unopened in detective offices.

10. Sniffer dogs

Not an ‘object’ but police dogs were introduced into regional police forces in the early 1900s to aid crime detection as well as to protect their beat officers. Airedale terriers were the preferred breed, as they were as efficient as bloodhounds in tracking suspects but cheaper to buy. Early adopters of sniffer dogs included Liverpool City Police, who added eleven Airedales to their force.

I uncovered all this information in my doctoral research into regional detective practice, which I will delve into further in future posts. But before that, in this week’s The Confidential Files, I’ll be sharing some of the more unusual and surprising crime detection-related objects and evidence I found in the archives, such as crime scene aids, bloodstained clothing and even a bullet, which caused quite a stir at the National Archives.

Next time in The Detective’s Notebook, I’ll be dipping my toe into the legendary and controversial case of the Whitechapel murders. I’ll be sharing the research I undertook for two chapters in a new, academic handbook on Jack the Ripper studies, which is due to be published soon.

Thank you, this is fascinating. Objects provide such an intriguing window into other times.

Very cool! I love your fingerprint kit - color me jealous!