Constable Dickens

Exploring Victorian Liverpool's underworld

My first research trip for my PhD study into Victorian detectives was to Liverpool, where I followed in the footsteps of my favourite Victorian author Charles Dickens, who had explored the city 160 years earlier. Ever the urban explorer, Dickens signed up as a special constable and ventured into some of the city’s most dangerous quarters. He used his experiences as inspiration for ‘The Uncommercial Traveller’, series of semi-autobiographical articles for All the Year Round.

Heading north

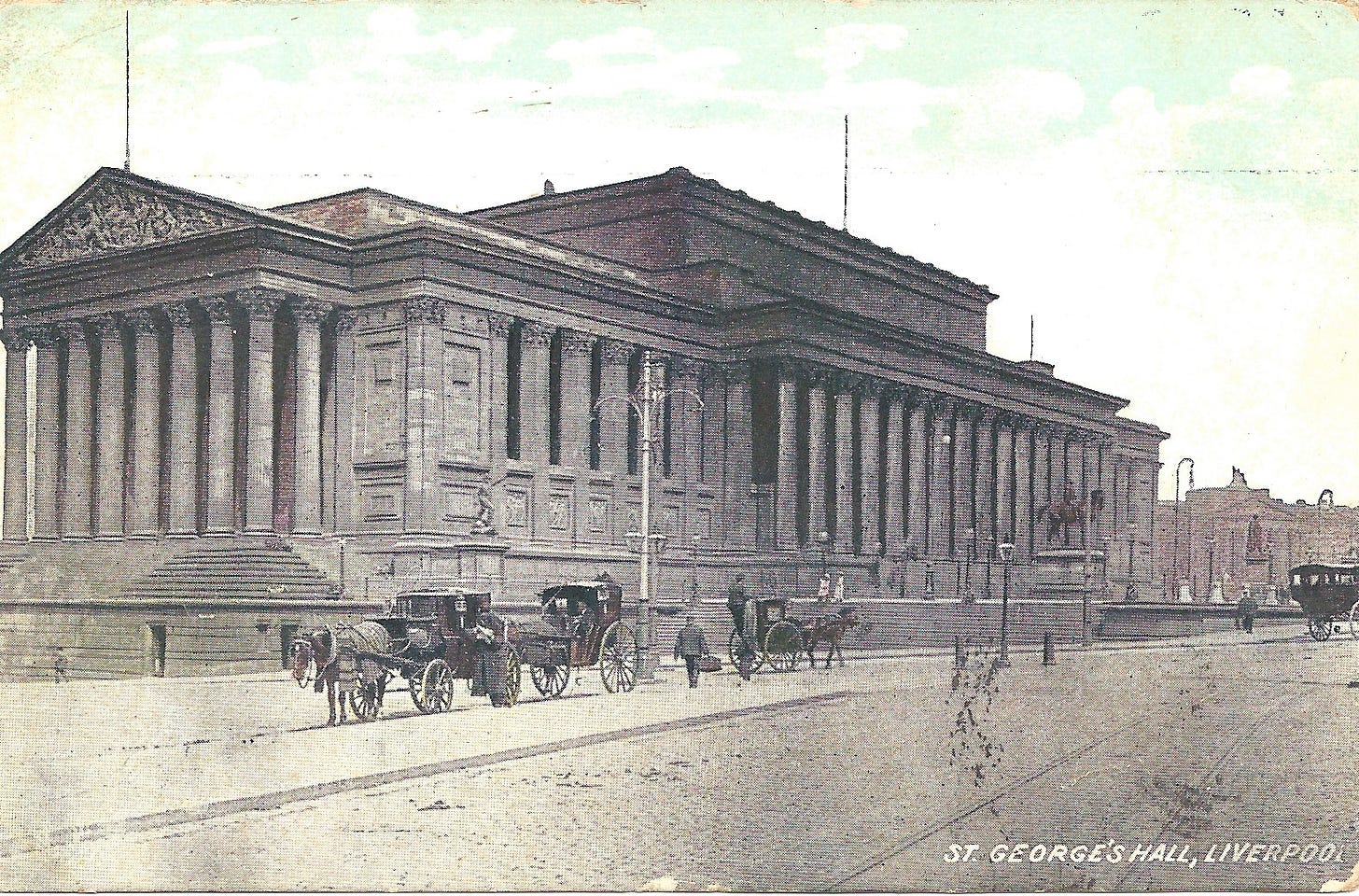

Dickens’ first known visit to Liverpool was in 1838, when he was 26 years old. Over the next two decades, he travelled to the city many times on his provincial tours, giving public readings and speeches in venues such as St George’s Hall. In 1844, the writer addressed an audience of 1,300 at the Mechanics’ Institute. During the visit, he spent time with his sister Fanny, drank champagne on the SS Britannia, and danced the night away at a party. On a more serious note, Dickens also relished the opportunity to visit the ‘darker’ side of a city, where he would gather valuable material for his non-fiction articles. To this end, he explored the Liverpool docks, under police supervision, in 1860.

The Liverpool Borough Police was formed on 9 February 1836, with 390 officers in two divisions. By 1860, there were 1,002 constables. The annual inspection stated that the force was ‘a highly respectable and effective body of men’. The chief constable was Captain Major John James Grieg, who had been in post for eight years. In February 1860, Dickens arranged with Chief Constable Grieg to attend a night-time patrol in the northern division, ‘that part of the borough offering a wide field for Mr Dickens’s observation than the south end of the town.’ The intrepid writer signed on as a special constable and set out on his ‘slumming experience’.

Dickens undercover

The first tasks of Dickens’ fictional narrator were to take a photograph of a suspected thief at the police headquarters, and to attend the daily police parade. At 10 pm, he took up a lantern and accompanied a superintendent (likely to have been Benjamin Ride) on his nightly tour:

In Mr Superintendent I saw, as anybody might, a tall, well-looking, well-set-up man of a soldierly bearing, with a cavalry air, a good chest, and a resolute but not by any means ungentle face.

The pair began by exploring sailors’ haunts, in ‘the obscurest streets and lanes of the port’, which were particularly treacherous after dark. The superintendent carried a thick walking stick, made of hard wood, and, when he struck it on the pavement, three constables appeared out of the shadows to await instructions. Dickens described how one was highly skilled in opening doors ‘as if they were keys of musical instruments’. Fully expecting to find stolen goods, the police officer had a knack of placing his body in the open door to prevent its being shut.

The group checked several ‘miserable places’ along their patrol, including the lodgings of sex workers and ‘crimps’ (a person who entraps men into shipping), and even a yard where a man was murdered. They visited a pub concert room, where sailors went for entertainment. Present were men from many different countries, including America, Malta, Finland and Spain, all smoking and drinking. As the night wore on, the ‘uncommercial traveller’ and his fellow police officers explored the labyrinth of ‘dismal courts and blind alleys,’ some of which were so dark that they had to feel their way along the passages with their hands. They saw women huddled over meagre fires, with their ragged clothes drying by the thin flames. Skinny children were asleep in dust heaps, apparently unaware of the stench and poverty around them. Like Dickens, the narrator would remember this ‘strange world, where nobody ever goes to bed,’ in his dreams.

Liverpool legacy

Charles Dickens published this semi-fictional account of his night in Liverpool in the article ‘Poor Mercantile Jack’ in his magazine All the Year Round, on 10 March 1860. Through his writing, he was fulsome in his praise of the police, which he described as ‘an admirable force…it is composed, without favour, of the best men that can be picked, it is directed by an unusual intelligence’. Dickens’ visits to Liverpool are commemorated on a plaque in the courtyard of the former Campbell Street Bridewell, which opened in early 1862. It carries a quote from Dickens, which expresses his love for the city: ‘Liverpool lies in my heart, second only to London.’ The site is now a bar, Furnival’s Well, which still has the original cells and their heavy prison doors. When I visited the pub, I told the landlord that I was interested in Dickens’ visit, and he showed me around!

Charles Dickens features in my new book, The Bermondsey Murder.