Location has always been a key factor in my inspiration for writing and all my books (so far!) are directly related to the places where I’ve lived. My first book was set in the Victorian underworld of my home city of Manchester, and my current home provides the backdrop for my latest publication. For me, local history, family history and crime history are intrinsically linked.

Criminal roots

My investigations into the exceptional life and groundbreaking detective work of Jerome Caminada began with my own family. I was born in Manchester and my roots are firmly in the city. When my great-grandparents migrated from the sun-drenched fields of Italy to settle in the grey slums of Ancoats in the 1880s, Detective Chief Inspector Caminada was a local celebrity. As soon as I read his memoirs I knew I had to write about him to bring this extraordinary man back to life after a century of obscurity.

Jerome Caminada was born on 15 March 1844 in Deansgate, Manchester, opposite the Free Trade Hall. His parents were both from immigrant families; his father was an Italian cabinetmaker and his mother had Irish origins. Caminada never lost his mixed cultural heritage, as noted in the Daily Mail:

He was in appearance a typical Italian with very strongly marked features, but he never lost his native Lancashire speech, and was in many ways very much a Lancashire man until the end of his days’.

After surviving a precarious childhood, during which he lost his father and several siblings to disease and endured grinding poverty, Caminada joined the Manchester City Police Force in 1868, at the age of 23. His career in fighting crime had begun.

For the next thirty years, Jerome Caminada worked tirelessly to clean up the crime-infested streets of Victorian Manchester. Showing an early aptitude for detective work, he was soon promoted to the detective department, which operated from Manchester Town Hall. A master of disguise and an expert in deduction, Caminada tackled many shady characters and nefarious criminals in his daily work in the city’s dark underworld, including desperate thieves, clever con artists, expert forgers and even coldblooded murderers. Many of his cases bear the hallmarks of the stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and, during his lifetime, he was often compared to his fictional counterpart.

Home sweet home

I moved even closer to my home for my book about the murder of PC Nicholas Cock, in 1876. He was fatally shot a few yards from my childhood house, a century before I moved there in the early 1970s. This investigation gave me the opportunity to rediscover the locality of Old Trafford, where I lived until I left home at the age of 18.

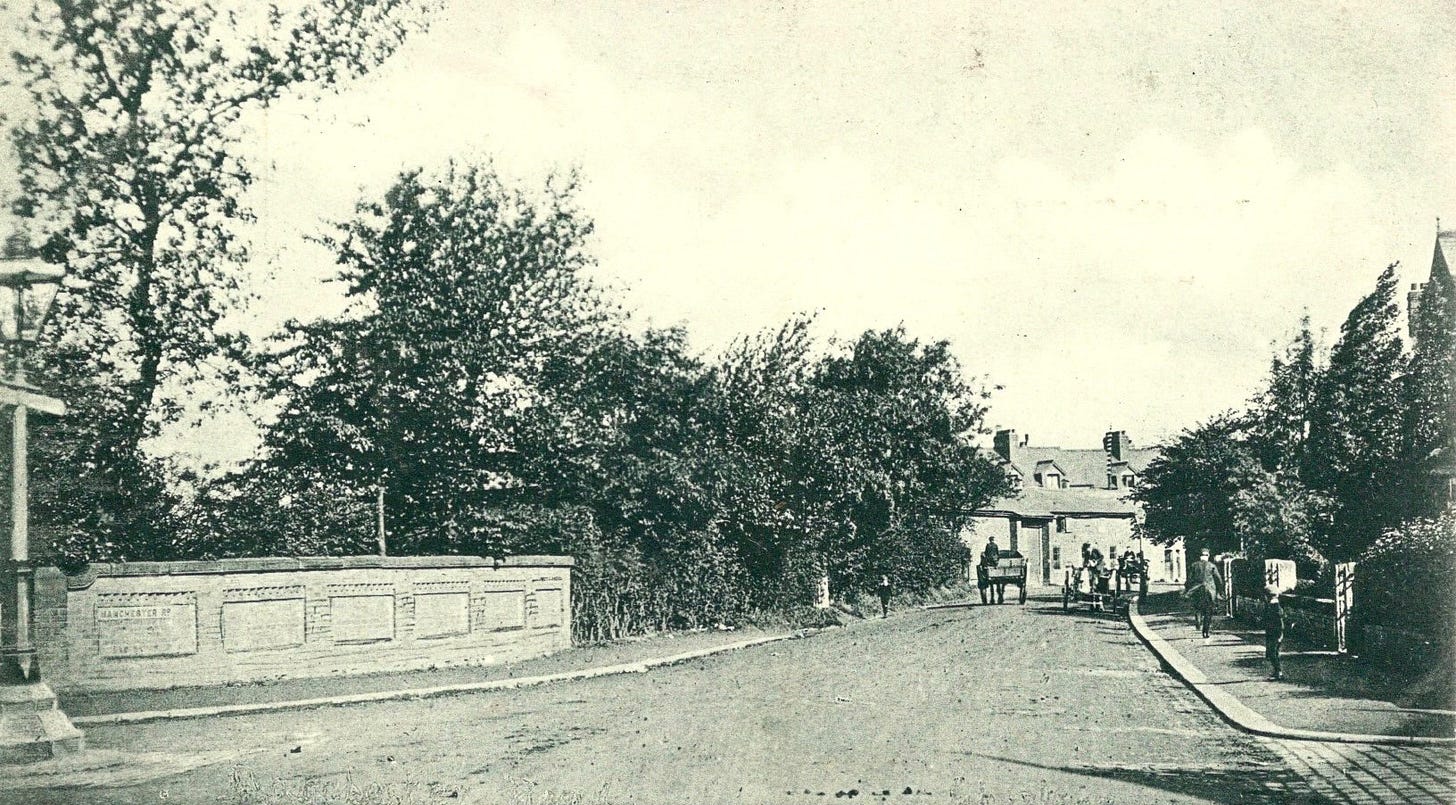

Just before midnight on Tuesday 1 August 1876, PC Nicholas Cock was patrolling his regular beat near West Point – he was walking up Manchester Road, towards the junction. It was a cloudy, but dry evening and there was little moonlight. The police officer was walking along a wide footpath, overhung with trees. The end of his beat was at the junction, which he was just approaching. Two men joined him for the final few yards: one was PC James Beanland and the other a law student, John Massey Simpson, who was on his way home after a night out. After exchanging pleasantries, Simpson left the others and continued on his way.

He was about 150 yards away when he heard two loud shots ring out. Simpson turned round to see flashes of light behind him in the pitch black. Hearing screams of, ‘Oh, murder, murder; I’m shot, I’m shot’, he rushed back to the spot to discover PC Cock slumped on the pavement near the garden wall of a large house. Even in the dim light, Simpson could see the unmistakable stain of blood spreading across his chest – Nicholas Cock had been shot.

Irish labourer William Habron, aged 19, was convicted of his murder mostly due to threats he had previouasly made against the rather zealous young police officer, during his routine duties – William and his two brothers liked a drink and they regularly crossed paths with PC Cock. Three years later, in an unexpected twist, a startling confession by a notorious burglar, as he faced the gallows for a murder, turned this extraordinary case around, and the real killer of Nicholas Cock was finally revealed.

A sinister connection

My ‘darkest’ and most emotive book was set in my adopted town of Reading, where I lived for 25 years. After I first moved there, I was researching local history when I came across the shocking case of the notorious Victorian baby farmer, Amelia Dyer, whose crimes were uncovered in 1896, when several bodies of infants were found in the River Thames at Caversham, close to where I was living and where I used to take my young children to play.

On Monday 30 March 1896, bargeman Charles Humphreys was navigating up the River Thames near Reading, towing a boat of ballast. He had passed the mouth of the River Kennet, where it flows into the Thames at Sonning Lock and was moving slowly towards the open fields of King’s Meadow recreation ground on his left. As he approached the wooden footbridge, known as the Clappers, he spotted a brown paper parcel floating in the water. Charles and his mate slowed the boat down to investigate and, leaning over the side with a hook, they dragged the package through the water towards them. Once on the towpath, Humphreys’s companion unravelled the damp parcel, which had been tied with macramé twine. He cut through two layers of flannel and pulled back the sodden fabric to expose a child’s foot and part of a leg.

Recoiling, Charles Humphreys quickly closed the parcel and ran straight to the police station. Later, at the mortuary, a police officer unwrapped the parcel, revealing the body of a baby girl. She was aged between six months and one year, swaddled in layers of linen, newspaper, and brown paper. Around her neck was a piece of tape, knotted under her left ear – she had been strangled and her body had been weighted down with a brick. On part of the wrapping was faint writing which provided the first clue.

The parcel was eventually traced to Amelia Dyer, who had moved to Caversham with her family the previous summer. As a baby farmer, she advertised in the local newspapers for children to foster, and several infants were brought to her two homes in Reading. They disappeared soon after. It is estimated that Dyer killed some seven children while she lived in the town but, as she had been plying this heinous trade for some 30 years, the actual number of children who died by her hand could have been in the hundreds.

Amelia Dyer was convicted of the murder of two children, Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons, in May 1896. Her crimes have left an indelible mark on Reading’s history, and there are still residents who remember their mothers and grandmothers warning them that if they did not behave, ‘Old Mother Dyer’ would deal with them. The paths around the Thames, where she walked, remain unchanged and, on a dark night, it is not difficult to imagine her with her long cloak carrying out her terrible deeds.

My latest book is set in Bermondsey, south-east London, which is where I spend much of my time now. You can find out about how my connections to this area inspired me in my free online talk, Murder in the Neighbourhood, for this year’s family history event, All About That Place 2024.

This event will take place at 7 pm on Sunday 6 October. Just click the link above for further information.